What We Mean by “Jōmon” and “Yayoi”

Archaeologists use Jōmon (“cord-marked”) to describe Japan’s long pre-agricultural era, famous for its pottery stamped with twisted cords and for a lifeway centered on fishing, hunting, and gathering. In broad strokes, Jōmon spans from the end of the last Ice Age (after about 14,000 BCE) to roughly 300 BCE. The Yayoi period follows (textbooks often give 300 BCE–250 CE, though in parts of northern Kyūshū it may start earlier), marked by the arrival and spread of wet-rice agriculture, metals, and new forms of social organization.

Those dates hide an important fact: Japan is big and rugged. The shift from foraging to farming began in the west and south and took centuries to ripple into the east and north. For a very long time, fishermen in one valley and rice planters in the next could be living in different worlds.

The Jōmon World: Abundance, Skill, and Stability

Imagine coastlines stippled with shell middens, cedar and chestnut forests managed like gardens, and rivers thick with salmon. This was the Jōmon environment: a post-glacial archipelago that rewarded people who knew when and where resources peaked. Jōmon communities built pit dwellings clustered in villages, some occupied for centuries. They crafted one of the world’s earliest ceramic traditions, making deep pots for boiling and leaching tannins from acorns, sleek vessels for stews and broths, and ornate pieces whose flamboyant rims still astonish.

Jōmon artisans were also virtuosos in lacquerwork, basketry, and cordage. They carved bone fishhooks, made stone tools of exquisite polish, and fashioned dogū—small humanlike figurines—whose broken bodies archaeologists often find deliberately deposited, perhaps as part of healing or fertility rites. There were stone circles in places like Ōyu (Akita) that hint at communal ceremony and calendrical observation. Trade moved obsidian, shells, and ideas along the coasts and across mountain passes.

For a society without fields, Jōmon people were not “simple.” They practiced landscape management—favoring nut trees, clearing underbrush, timing burns—so food returned predictably. In some regions (famously at Sannai-Maruyama in Aomori), evidence for chestnut groves suggests intentional arboriculture: a kind of proto-cultivation that let large villages flourish.

Why Change Came: Currents Across the Sea

Two forces nudged the archipelago toward farming. First, contact and migration from the Asian mainland—especially the Korean peninsula—brought new crops, new tools, and new ways to live. Second, the package that arrived—wet-rice agriculture with its irrigation, transplanting, bunds, and canals—offered something powerful that mere foraging or dry-field gardening could not: reliable surplus.

Rice was not just a plant; it was a system. It required coordinated labor to build and maintain paddies, to manage water, and to schedule transplanting and harvests. It encouraged fixed residence, granaries, and rules about who controls the water. Inevitably, that meant leaders, specialists, and stratification.

The Yayoi Package

Archaeologically, the first Yayoi signatures appear in northern Kyūshū: plain-surfaced pottery different from Jōmon cord-marking; paddy fields traced by ditches and field ridges; raised-floor granaries; and metals—bronze (for ritual items and prestige goods) and iron (for tools and, increasingly, weapons).

From there the complex spread east along the Seto Inland Sea and up the main island of Honshū, reaching the Kantō region generations later. Classic sites tell the story:

- Itazuke (Fukuoka): early paddies and village layout.

- Yoshinogari (Saga): a vast moated settlement with watchtowers, palaces, workshops, and graveyards that distinguish elites from commoners—evidence for chiefdom-level politics.

- Toro (Shizuoka): beautifully preserved paddy plots, irrigation channels, and toolkits that reveal day-to-day farming.

Yayoi paddies were engineered landscapes. Farmers transplanted seedlings from nurseries into flooded plots, controlled flows with sluices, and harvested with short iron or bamboo sickles. They stored harvests in granaries safe from rodents and damp. The work was hard and seasonal, but the payoff was population growth, settlement density, and the accumulation of wealth that could be displayed—and defended.

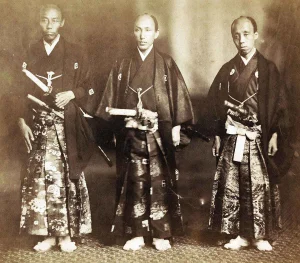

Hierarchy, Warfare, and Exchange

With fields came property, and with property came politics. Yayoi cemeteries show status differences: some graves furnished with bronze mirrors, swords, halberds, and ornaments, others with little. Around settlements, archaeologists find moats, palisades, and watchtowers—a language of defense. Skeletal remains sometimes carry trauma marks from arrows or blades. Conflict might have been over land, water rights, or regional rivalries between ambitious chiefs.

At the same time, the archipelago plugged into wider exchange. Bronze casting—famous for dōtaku (thin, tall bronze bells)—flourished, especially in Kansai and Shikoku. Iron trickled in first as imports and then via local working, transforming agriculture (axes, hoes) and craft (chisels, knives). Prestige goods—mirrors from the continent, jewelry, specialized pottery—moved along maritime routes, binding polities into networks of alliance and competition.

From Dogū to Dōtaku

Jōmon ritual life was anchored in dogū figurines, stone circles, and deposits that seem to encode healing, fertility, or ancestor concerns. In the Yayoi era, the material language changes. Dōtaku bells, often buried in groups on hilltops, suggest seasonal rites linked to agriculture—calling or thanking the rice spirit, marking the rhythm of planting and harvest. Jar burials become common; in some regions, individuals were interred in large ceramic coffins (kamekan), sometimes flexed, sometimes extended, sometimes with goods that signal rank. Wooden tally sticks, ritual bronze weapons with little practical use, and mirror deposits round out a ceremonial world built around surplus and seasonality.

It would be wrong to picture an abrupt spiritual revolution. Old and new coexisted. Many Yayoi villages stood on or near Jōmon sites, and practices almost certainly blended. Ideas that later feed into Shintō—reverence for kami in rocks, groves, and water; the link between purity and agricultural fertility—are easier to imagine in a Yayoi landscape of paddies, but their roots run deeper.

Who the People Were

For decades, scholars have described Japan’s past population history as a “dual structure”: a long-resident Jōmon ancestry blending with incoming continental ancestry associated with Yayoi rice farmers. Ancient DNA now broadly supports significant migration from Northeast/East Asia during the Yayoi era, followed by admixture whose proportions vary by region and period. In the far north (Hokkaidō), where full wet-rice farming was impractical, Epi-Jōmon lifeways persisted and later transformed into the Satsumon culture; over very long arcs, these northern traditions are connected to the emergence of the Ainu. In the Ryūkyū islands, different blends appeared again. The archipelago’s biological story matches its archaeology: layered, regional, and long-running.

Continuity and Contrast in Daily Life

What changed from Jōmon to Yayoi when you woke up in the morning?

- Foodways: Stews of fish, nuts, and roots gave way, in many places, to rice as a staple, complemented by millets, beans, and continued use of marine foods. Salt making, brewing, and new forms of fermentation likely expanded.

- Labor rhythms: The forager’s calendar—following salmon runs, nut drops, and shellfish tides—shifted toward communal agricultural schedules: transplanting, weeding, draining, harvesting, threshing, storing.

- Houses and villages: Pit dwellings remained, but raised-floor buildings appeared for storage and ceremony. Moats and palisades re-organized space and signaled power.

- Tools and textiles: Iron blades and hoes eased tasks; looms and spindle whorls hint at more woven clothing, perhaps changing costume, status display, and gendered divisions of labor.

Continuity mattered too. Fishing technology, shellfish gathering, nut processing, and the know-how of rivers and tides did not vanish. The Yayoi “revolution” grew fastest—and stuck hardest—where newcomers could mesh rice with existing coastal abundance.

Regional Mosaics and Borderlands

Because Japan is a chain of mountains and seas, the Jōmon-to-Yayoi shift produced patchworks rather than uniformity. Kyūshū and the Inland Sea saw early, dense Yayoi fields and politics; Kansai developed elaborate bronze rites; Kantō adopted paddies later and on different scales; Tohoku and Hokkaidō retained a stronger foraging signature for centuries. Even within a single river system, upland hamlets might keep Jōmon craft habits while lowland villages dug ditches and stacked grain.

That mosaic is a reminder: history is rarely a switch flicked once, everywhere.

A Few Sites as Windows Into Change

- Sannai-Maruyama (Aomori, Middle Jōmon): Large, long-lived village with pit dwellings and monumental post structures, evidence for planned spaces, and managed chestnut groves—a high-energy forager settlement that thrived without fields.

- Ōyu Stone Circles (Akita, Late Jōmon): Twin megalithic rings aligned with solar events, accompanied by artifact clusters that look like ritual stations—community, time, and belief inscribed into stone.

- Itazuke (Fukuoka, Early Yayoi): Early paddy fields and a settlement plan showing the basic kit of Yayoi life—fields, ditches, storage, and houses.

- Yoshinogari (Saga, Middle–Late Yayoi): A sprawling moated town with watchtowers, craft zones, and cemeteries that neatly display status, often read as the capital of a regional chiefdom plugged into continental trade.

- Toro (Shizuoka, Late Yayoi): Paddy fields so clearly preserved that their plots, ridges, and channels can be mapped—an agricultural textbook in the ground.

The Long Arc to Kofun

By the late 2nd to 3rd century CE, some Yayoi polities had grown into powerful regional centers. Chinese histories mention the people of Wa and a shaman-queen named Himiko, hinting at diplomacy across the sea. In Japan, we begin to see the earliest keyhole-shaped tombs that define the Kofun period—monumental mounds for kings and queens with grave goods that shout sovereignty. The path from village paddies to royal tumuli runs through Yayoi granaries, moats, and councils by the water gate.

Rethinking “Revolutions”

It is tempting to call Yayoi a “revolution.” In some valleys, that’s exactly how it felt: new people, new crops, new weapons, new rules. Elsewhere, it was a slow synthesis, a graft of paddies onto deep Jōmon expertise in reading landscapes and seasons. The real lesson is that technological change happens in social ecologies. Rice didn’t triumph because it is “better.” It triumphed where people could organize water and labor, defend fields, and find meaning in the work through ritual and story.

Why This Story Still Matters

Modern Japan’s cuisine, festivals, and even vocabulary carry Yayoi fingerprints—rice as staple and symbol, irrigation cooperatives, seasonal rites. Yet the Jōmon inheritance is just as profound: craft virtuosity, environmental knowledge, and a sense that mountains, rivers, and coasts are alive with presence. The history of Jōmon and Yayoi is therefore not a tale of winners and losers but a double lineage: a forager’s intimacy with place woven into a farmer’s choreography of water and time.

From hunter-gatherers to rice farmers is a neat phrase. On the ground, it was messier and richer: a centuries-long negotiation between old skills and new systems, written in clay, bronze, water, and grain—out of which a distinctive civilization took shape.