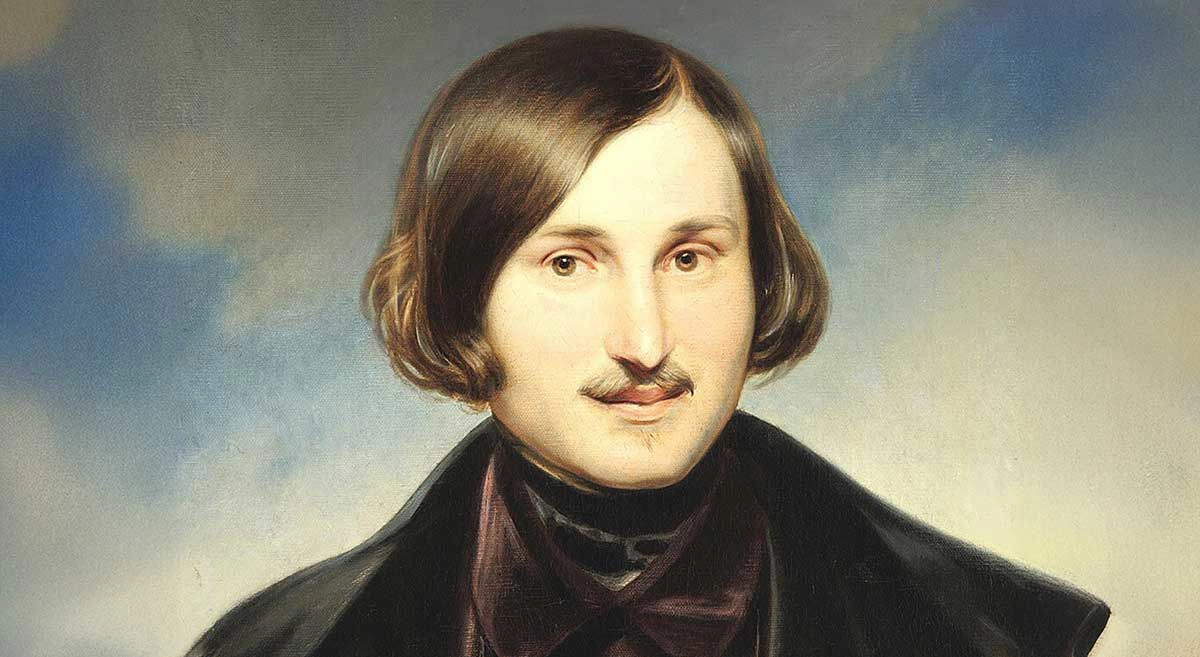

Nikolay Gogol sits in a strange place in literary history. He was born in Ukraine, became famous in Russia, mocked the tsarist system with merciless satire—then spent his final years defending the very state and Church his readers thought he was attacking.

His life and work are full of contradictions, which is exactly what makes him so fascinating.

A Ukrainian Beginning

Gogol was born in 1809 in the small town of Sorochyntsi in Ukraine, into a minor gentry family with Cossack roots. His father, Vasily Gogol-Yanovsky, was both a landowner and an amateur playwright, so young Nikolay grew up surrounded by storytelling, folklore, and theatre.

He learned Ukrainian, Russian, and Polish, a sign of the mixed cultural world he belonged to. At eleven, he left home to study at a school in Nizhyn, and in 1828 he set off for St. Petersburg, chasing the dream that draws so many young writers: literary fame in the imperial capital.

His first attempt was a disaster. He self-published a Romantic poem called Hans Küchelgarten, received brutal reviews, panicked, bought back the copies, and destroyed them. It was a humiliating start—but not the end.

In 1831, he finally broke through with Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka, a collection of Ukrainian stories full of ghosts, fairs, Cossacks, and village life. The great poet Alexander Pushkin admired it, and Gogol followed up with another volume in 1832. For a time, he was known mainly as the Ukrainian storyteller of St. Petersburg.

Taras Bulba and the Ukrainian Past

Gogol’s early 1830s work leaned hard into Ukrainian history and legend. In Mirgorod (1835), another two-volume collection, he published Taras Bulba, a historical novella set during the 17th-century Khmelnytsky Uprising against the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

The hero, Taras Bulba, is an aging Cossack warrior whose hatred of the Poles is so fierce that he kills his own son Andriy for fighting on the Polish side. In a later 1842 revision, Gogol added an ending in which Taras is captured and burned at the stake.

This story, like much of his early work, blended nationalism, folklore, and violence. But even as he wrote about Ukrainian heroes, Gogol himself was drifting away from his Ukrainian identity in public life. After the Polish Uprising of 1830 and the wave of anti-Polish feeling that followed, he quietly dropped the Polish-sounding part of his surname, Yanovsky.

A Professor Who Wasn’t a Professor

While he was building his literary career, Gogol took assorted minor government jobs. In 1834, he tried to secure a post as professor of Ukrainian history at the new university in Kyiv. He was rejected.

Instead, he was made professor of Medieval History at the University of St. Petersburg—despite having no real qualifications. He neglected his students, focused on his writing, and quickly realized he was out of his depth. By 1835, he resigned.

But that same year, he began his true transformation: from “Ukrainian tale-spinner” into one of the sharpest satirists of the Russian Empire.

The Nose: Bureaucracy Gets Surreal

In 1836, Gogol published The Nose in Pushkin’s journal The Contemporary. It’s a short story with a completely absurd premise:

- A barber discovers that someone’s nose has been baked into a loaf of bread.

- The nose belongs to Collegiate Assessor Kovalyov, a low-ranking bureaucrat.

- Kovalyov wakes up with a flat space where his nose should be—and then spots his nose walking around the city dressed as a high-ranking official.

The nose refuses to return to his face and even outranks him in the bureaucratic ladder.

It’s funny, grotesque, and deeply symbolic. The higher rank of the nose exposes how obsessed the system is with titles and status. For Kovalyov, the real outrage isn’t the horror of losing part of his body—it’s that his own nose is now a more important official than he is.

Gogol’s fascination with noses shows up all over his writing—through smells, sneezing, snuff, and snoring. He himself had a large, memorable nose; critics like Vladimir Nabokov loved to point out the connection.

The Government Inspector: “You’re Laughing at Yourselves”

Gogol’s true breakthrough came with his play The Government Inspector, first performed in 1836 at the Alexandrinsky Theater in St. Petersburg.

The story is simple and brilliant:

- In a small provincial town, corrupt officials hear that an undercover government inspector is coming.

- Panicked, they scramble to cover up their crimes.

- They mistakenly decide that a useless, debt-ridden visitor named Khlestakov must be the inspector.

- Khlestakov quickly realizes the mistake and milks it—accepting bribes, boasting about his imaginary closeness to Pushkin and the tsar, and flirting with the mayor’s wife and daughter.

Eventually he leaves town with his pockets full, and only later do the officials learn they’ve been fooled. As their anger boils over, the mayor turns to the audience and says the famous line:

“What are you laughing at? You’re laughing at yourselves!”

Censors were nervous. The play mocked corruption at every level of local administration. It was only performed after Tsar Nicholas I personally approved it—and even came to see it. He reportedly enjoyed it and said, “Everybody got his due, I most of all!”

Critics like Vissarion Belinsky praised the play for confronting real social problems instead of painting a rosy picture of Russia. Others accused Gogol, the Ukrainian outsider, of mocking the Russian people. Gogol denied that he was attacking Russia as such. He claimed he was exposing universal human corruption, waiting to be set right by a “real” inspector—that is, by higher moral judgment.

But the controversy shook him. Shortly after, he left Russia.

Dead Souls: Buying What Doesn’t Exist

In the late 1830s, Gogol settled in Rome, where he began working seriously on his masterpiece: Dead Souls.

The premise revolves around a loophole in the Russian system of serfdom:

- Serfs (“souls”) are counted in periodic censuses and are taxed.

- If a serf dies between censuses, the landowner must still pay tax on that dead soul until the next count.

Enter Pavel Chichikov, a smooth operator with a bizarre plan. He travels around the countryside offering to buy these dead souls:

- Landowners are relieved to get rid of tax burdens and sometimes even give the dead souls away for free.

- Chichikov plans to gather hundreds or thousands of them on paper.

- Then he will use them as collateral for loans and build his fortune on “people” who no longer exist.

On the surface, no one seems to get hurt: the landowners save money, the state still receives taxes, and Chichikov profits. But the absurdity of the scheme highlights something darker: a system where human beings can be reduced to numbers, traded, and used as abstract financial units.

Dead Souls came out in 1842. Many readers saw it as another attack on the Russian character. Gogol insisted it was only the first part of a larger plan, modeled after Dante’s Divine Comedy, in which Chichikov would eventually be redeemed in later volumes. He worked for years on the second part—then destroyed it.

The Overcoat: From Laughter to Pity

The same year, 1842, Gogol published what many consider his most perfect short story: The Overcoat.

Its hero is Akaky Akakievich, a low-level clerk in St. Petersburg whose job is copying documents by hand. He:

- Has no ambitions.

- Is mocked by his coworkers.

- Owns an overcoat so worn out that even the tailor says it can’t be repaired.

Akaky slowly saves every kopeck he can, denying himself warmth and comfort, until he can afford a new coat. When it finally arrives, it transforms his life. His colleagues admire it so much that they throw him a party.

On his way home from this brief moment of happiness, Akaky is mugged. Two men steal the overcoat. His attempts to get help from the police go nowhere. A bureaucratic “important personage” berates him for daring to bother a man of his rank with such a trivial matter.

The shock and stress prove fatal. Akaky falls ill and dies.

After his death, rumors spread of a ghost haunting the streets and stealing overcoats from passersby. Eventually, the ghost confronts the same important personage and takes his coat.

The story begins in a comic tone, making Akaky an object of ridicule. Slowly, almost imperceptibly, Gogol shifts the mood until the reader feels pity instead of laughter. The target of the satire is no longer just a pathetic clerk but a system that crushes insignificant people without a second thought.

Later writers felt Gogol’s influence deeply. Fyodor Dostoevsky is often (perhaps apocryphally) credited with saying: “We all came out from under Gogol’s Overcoat.”

Faith, Doubt, and the Burning of Dead Souls

After 1842, Gogol’s life grew more troubled.

He traveled restlessly across Europe, usually returning to Rome as his base. He worked on the second part of Dead Souls but grew increasingly anxious about his own work. Influenced by religious thinkers and mystics, he began to see the grotesque and absurd elements of his stories as sinful, even demonic.

In 1847, he published Selected Passages from Correspondence with Friends, a book that stunned his earlier admirers. In it, Gogol argued that the remedies for Russia’s problems lay in obedience to the state and the Church, not in exposing flaws through satire. For many readers, this sounded like a retreat from the critical spirit of his own work.

Belinsky responded with a furious letter attacking serfdom, hypocrisy, and Gogol’s new conservatism. It became one of the most famous documents of Russian literary criticism.

In 1848, Gogol went on pilgrimage to the Holy Land, hoping for spiritual renewal. But his physical and mental health continued to decline. By 1852, deeply depressed and tortured by religious scruples, he burned the manuscript of the second part of Dead Souls.

Soon after, he stopped eating, took to his bed, and died in Moscow on March 4, 1852, at just 43 years old.

A Difficult, Lasting Legacy

Gogol was first buried at Danilov Monastery in Moscow. When the monastery was shut down in the Soviet period, his remains were moved to Novodevichy Cemetery, among other Russian cultural giants.

He left behind:

- Ukrainian tales rooted in folklore and Cossack history

- Surreal, darkly comic stories like The Nose

- Social satires like The Government Inspector and Dead Souls

- Deeply humane, tragic pieces like The Overcoat

And he left behind contradictions:

- A Ukrainian-born writer who became a central figure in Russian literature

- A relentless satirist who later defended the very powers he seemed to criticize

- A master of the grotesque who ended up fearing his own imagination

Maybe that’s why Gogol’s work still feels alive: it never lets the reader stay comfortable. Under the jokes, ghosts, and wandering noses, he is always asking uneasy questions—about power, hypocrisy, small lives crushed by big systems, and the strange ways a human soul can break under the weight of its own conscience.