In the early 260s BCE, an old dream flickered back to life in Greece.

Athens and Sparta – the two great city-states that had once decided the fate of the Persian Empire and fought each other for hegemony – tried one last time to shape the future of the Greek world. But this time, they couldn’t do it alone. They reached out to a new kind of power: a Hellenistic king ruling from faraway Egypt.

The result was the Chremonidean War (c. 267–261 BCE) – a conflict that most people have never heard of, yet one that quietly marked the end of an era. It was the last time the traditional, independent city-state (the polis) stood at the center of international politics. After this, the stage belonged to kings and federations, not to single cities like Athens or Sparta.

Macedonia’s Shadow Over Greece

To understand the war, you have to go back almost a century, to 338 BCE and the Battle of Chaironeia. There, Philip II of Macedon crushed the combined forces of Athens and Thebes. From that moment on, Macedon was the dominant power in Greece.

There were rebellions, of course:

- The Thebans tried to break free in 335 BCE and were utterly destroyed.

- Sparta rose against Alexander the Great around 331 BCE, only to be dismissed afterward as having fought a mere “war of mice.”

- After Alexander’s death, Athens and its allies fought the Lamian War (323–322 BCE), another failed attempt to restore old freedoms.

Each revolt was wrapped in the language of “Greek freedom,” but each was ultimately isolated: one city leading a few allies against a much stronger Macedonian machine.

Meanwhile, the Greek world slid into the chaos of the Wars of the Successors, as Alexander’s generals carved his empire into competing kingdoms. Macedon itself was battered in these struggles. By the end of the 280s BCE, however, a new ruler finally brought stability: Antigonus II Gonatas.

Antigonus was the grandson of Antigonus the One-Eyed and the son of Demetrius Poliorcetes – a man born into a family of ambitious warlords. After years of wandering and fighting, he managed to seize the Macedonian throne around 280/79 BCE and hold it for roughly forty years.

For Macedon, his reign meant stability and power. For the Greek city-states, it meant something darker: garrisons on their hills, Macedonian-backed tyrants in their councils, and the slow suffocation of their independence.

Athens & Sparta in a Hellenistic World

By the 3rd century BCE, the glory days of both Athens and Sparta were long gone.

Sparta: A King With Big Ambitions

Sparta’s decline had begun with its defeat by Thebes at Leuktra in 371 BCE. Its citizen body shrank, its rigid social system made it hard to recover, and it was often too weak to truly compete – which ironically sometimes saved it, as larger powers had bigger enemies to worry about.

Yet by the early 200s, Sparta began to stir again under King Areus I (c. 309–265 BCE). Traditionally, Sparta had two kings ruling at the same time, but Areus stood out as a strong, almost “Hellenistic-style” monarch:

- He issued Sparta’s first silver coinage with his own name and image.

- He appeared at pan-Greek sanctuaries like Delphi, projecting himself as a king on equal footing with other rulers of the Mediterranean.

Areus wanted Sparta back on the international stage – and the coming war would give him that chance.

Athens: Still Clinging to Democracy

Athens had a rougher time. Unlike Sparta, it was too rich, too strategic, and too tempting to be ignored. Its famous port at Piraeus, its shipyards, and its wealth made it a prize no king wanted to leave completely independent.

After the Lamian War, the city oscillated between moments of democratic revival and periods of oligarchy or tyranny enforced by foreign powers. Yet the Athenians never stopped trying to restore their democracy and autonomy.

In 286 BCE, they scored a symbolic win: they expelled the Antigonid garrison from the Museum Hill opposite the Acropolis and restored democracy. But it was only a partial victory. Macedon still held Piraeus and likely other strongpoints in Attica. The Athenians were free in name, but they were living under a constant reminder of Macedonian control.

The Chremonidean Decree: A Call to “Free Greece”

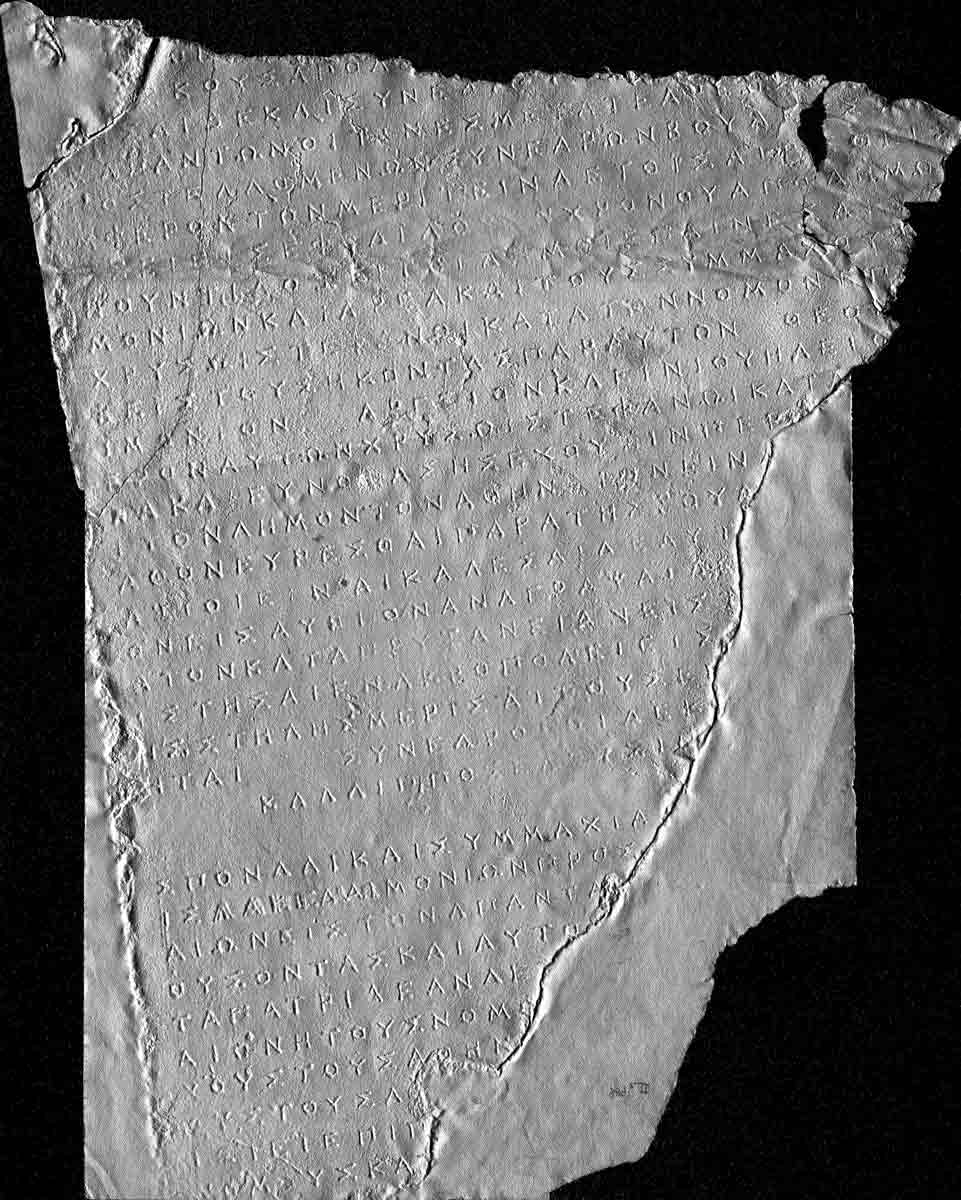

The war takes its name from Chremonides, an Athenian politician who proposed a crucial decree in 269/8 BCE. We know about it because the text was inscribed in stone and set up on the Acropolis – one of the rare direct windows we have into this period.

In that decree, the Athenian assembly announced:

- An alliance with Sparta

- A call to “free the Greeks” in the spirit of their joint struggle against Persia in 480–479 BCE

The document reveals the different motives behind the alliance:

- Athens wanted help driving Macedonian forces out of Attica and fully reclaiming its territory.

- Sparta, listed alongside its Peloponnesian and Cretan allies, sought the prestige of leading “Greece” again. King Areus is mentioned by name several times, showing how dominant he had become in Spartan politics and how central he was to the alliance.

But there was another major player.

Enter Ptolemy II: Egypt’s King With Aegean Ambitions

The decree also mentions King Ptolemy II Philadelphus of Egypt. The Ptolemies ruled from Alexandria, but their power stretched across the eastern Mediterranean. They and the Antigonids were rival naval and commercial powers, constantly bumping into each other’s influence in the Aegean Sea.

Ptolemy had already been helping Athens behind the scenes – offering grain in hard times and probably money to support Athenian resistance. Supporting an alliance of Athens and Sparta against Antigonus was perfectly in line with his interests: let the Greeks do the fighting while Egypt pulled the strings and weakened Macedon.

In many ways, the Chremonidean War was less a purely Greek uprising and more a Ptolemaic move in a great-power rivalry.

The War Begins: Areus on the March

The war started around 268/7 BCE. Antigonus responded quickly, moving against Athens with an army and a fleet. For roughly six years the conflict revolved around a prolonged struggle for Attica, with Athens effectively under siege.

Egypt sent help in the form of a naval commander, Patroclus, who set up fortified coastal bases like Koroni (modern Porto Rafti) and Sounion. These helped supply Athens and protect parts of the countryside, but his forces were too small to challenge Antigonus head-on. That job fell to the Spartans and King Areus.

To reach Athens from the Peloponnese, Areus had to pass the narrow isthmus controlled by the fortress of Acrocorinth, one of the strongest positions in Greece and held firmly by an Antigonid garrison. On top of that, the Antigonids seem to have built additional defenses in Attica to block any Spartan advance.

Areus probably tried to break through more than once – in 267, 266, and again around 265 BCE. On one occasion he actually reached Attica but had to turn back when his army ran low on supplies. The risks were too high for what he saw as limited gain “just for the sake of his allies.” That decision speaks volumes about the uneasy balance between idealism and self-interest in the alliance.

Finally, in 265 or 264 BCE, Sparta’s luck ran out. Areus marched again, only to be defeated near Corinth and killed in battle.

His death shattered Spartan hopes. Their fragile recovery had always depended on avoiding major disasters. With a tiny citizen body and a rigid social system that made it hard to replenish their numbers, they were always one decisive defeat away from collapse. The loss of Areus drove home just how vulnerable Sparta really was and helped set the stage for internal crises and reforms later in the century.

Athens Alone: The Long Siege

With Sparta effectively knocked out of the war, Athens was left to stand almost alone. Ptolemaic naval support continued, but never in overwhelming strength. For Egypt, Greece was a useful theater, not a core priority.

The Athenians endured years of hardship:

- Their port, Piraeus, was still in Antigonid hands, making food imports extremely difficult.

- Warfare in Attica took the shape of sieges, raids, and fights over fortified positions, as each side tried to control farmland and supply lines.

- Even with Ptolemaic coastal bases, it was a constant struggle just to feed the city.

At one point, diplomatic maneuvering briefly eased the pressure. In 263 BCE, Alexander of Epirus, an ally of Egypt, invaded Macedon itself. Antigonus had to turn north and agree to a temporary truce so he could deal with this new threat.

For Athens, that short window meant life. The citizens hurried to plant crops, hoping at last to rebuild their shattered food supply. But the relief was temporary. Alexander of Epirus was defeated, and by 262 BCE Antigonus was back in Attica.

When harvest time came, the Macedonian army was once more in control. With no allies left, no secure grain route, and no realistic hope of victory, Athens had to surrender.

Defeat and the End of an Era

The surrender in 262 BCE was a harsh blow:

- Antigonid forces reoccupied the Museum Hill overlooking the city.

- Athens’ democracy was not officially abolished, but it now operated under Macedonian supervision.

- Athenian silver coinage ceased; the city had to adopt Antigonid monetary policy.

- Leading figures suffered: Chremonides and his brother Glaucon fled to Alexandria, while the historian Philochorus was executed.

Culturally and politically, it felt like a closing chapter. Around the same time, Zeno of Citium – founder of Stoicism and a man whom Antigonus himself had admired – also died. For many Athenians, it must have seemed that a philosophical age, a political age, and an entire way of being Greek were ending together.

At sea, Antigonus likely later confirmed his dominance with a naval victory over a Ptolemaic fleet near the island of Kos (though the exact date is debated). Whenever it happened, that win symbolized Macedon’s firm grip on Greece and the central Aegean.

Why the Chremonidean War Matters

On the surface, the Chremonidean War looks like a failed revolt: two famous cities, another lost struggle for “freedom,” another round of garrisons and foreign oversight.

But its deeper significance lies in what it reveals about the changing Greek world:

- Athens and Sparta were no longer enough. Even together, and even with help from a major kingdom like Ptolemaic Egypt, they couldn’t break Macedonian power. The independent polis as a leading actor on the international stage was finished.

- Power was shifting to larger structures. After this war, future resistance to Macedon would come not from lone city-states but from federal leagues like the Achaean and Aetolian Leagues, which pooled the resources of many cities.

- The Hellenistic age belonged to kings and federations, not classical city-states. The Chremonidean War is the last flicker of the old world – the last serious attempt by the “classical” giants to reclaim their former place.

In short, the war marks the moment when Athens and Sparta stopped being protagonists in world affairs and became, instead, important but secondary players in a stage dominated by monarchs and leagues.

The names might be obscure, the sources frustratingly thin, and the dates sometimes debated, but the message is clear: in the 260s BCE, with famine inside the walls of Athens and a Spartan king lying dead near Corinth, the age of the independent Greek city-state quietly came to an end.

support our project

At History Affairs, we believe history belongs to everyone.

donateYour contribution helps us keep this global archive open, free, and growing — so people everywhere can learn from the past and shape a better future.

know the present

Defense Tech Needs the State, Not Less of It

Trump Era or The New Imperial Age

America First, Venezuela, and the Trap of Old Habits

Why the AI Race Has No Winner

reading more

America First, Venezuela, and the Trap of Old Habits

Aelfgifu: Queen of England and Denmark

Joyce Butler and the Long Road to the UK Sex Discrimination Act 1975

Why Athens Exiled Its Most Popular Politicians

Dunsterforce: The Race to Baku, 1918

The Incredible Inca Messengers: How Runners Connected an Empire

Thrace – Birthplace of Ares and Spartacus

William Wallace – The Saver of Scotland

The Nazi-Soviet Pact: A Deal with the Devil

The Women Who Turned Music Theory into Games

Players in the Guildhall

Versailles: From Hunting Lodge to World Icon