Lincoln didn’t go to Gettysburg to deliver a “great speech.” He went to do something far more practical: shape the meaning of the war while the war was still raging.

On November 19, 1863—four months after the bloodiest three-day battle of the Civil War—he was invited to a cemetery dedication and asked for “a few appropriate remarks.” What came out was fewer than 275 words. It took about three minutes.

And yet those three minutes were designed like a tool. Lincoln aimed it at the country’s exhaustion, the war’s rising death toll, and a shaky political future. He wasn’t just honoring the dead. He was trying to win the living.

So what did Lincoln hope to achieve? And how did those achievements echo forward into modern history?

1) He honored the fallen—but he did it in a strategic way

Yes, the event was a cemetery dedication. Lincoln had to acknowledge the thousands who had died. But notice what he didn’t do:

- He didn’t offer detailed battlefield drama.

- He didn’t praise generals.

- He didn’t drown the audience in grief.

Instead, he framed the dead as people who had already done something sacred: they had “consecrated” the ground through sacrifice. In other words, the ceremony wasn’t what made the place holy. The soldiers did.

That’s not just poetic. It’s political. It removes the spotlight from speeches and officials—and puts it on the meaning of sacrifice. Lincoln was saying: This is not a performance. This is a national reckoning.

2) He rewired the war’s purpose: from “saving the Union” to a “new birth of freedom”

This is the heart of the Gettysburg Address.

By late 1863, the Union needed more than military victories. It needed a moral storyline strong enough to keep people committed through more years of slaughter.

Lincoln reached backward to the Declaration of Independence—“all men are created equal”—and used that founding language to redefine what the United States was supposed to be. Then he pushed forward: the war was not merely a fight to restore a map. It was the painful process of giving the country a “new birth of freedom.”

That move mattered because many Americans still framed the conflict mainly as preserving the Union. Lincoln tied Union survival to something bigger: freedom itself, especially after the Emancipation Proclamation earlier that year.

He didn’t just say “we must win.” He implied: If we lose, the founding promise collapses.

3) He turned grief into a job for the living

Lincoln’s most urgent goal wasn’t memorializing the past. It was securing the future.

He told the audience, in effect: the dead have done their part; now you have work to do.

The speech is structured like a handoff:

- The soldiers gave “the last full measure of devotion.”

- The living must be “dedicated” to finishing the task.

That’s how he fought war-weariness. He didn’t deny the horror. He gave it a meaning—and then demanded commitment so those deaths would not be “in vain.”

This is why the address keeps resurfacing during moments of national stress. It’s a template: when a society is bleeding, you either quit—or you choose a purpose strong enough to continue.

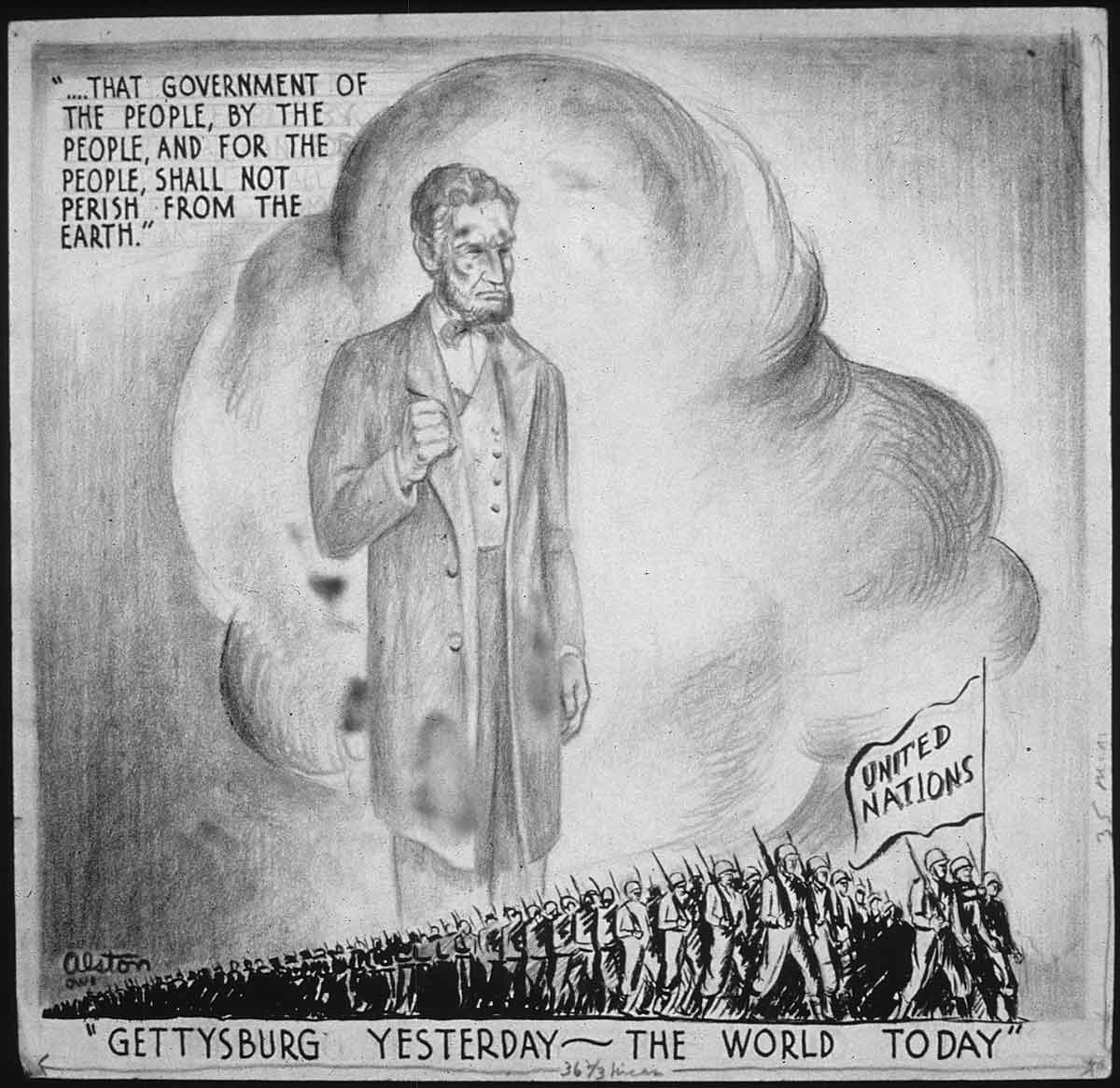

4) He redefined democracy as something the world is watching

The closing line isn’t just famous because it sounds good:

“government of the people, by the people, for the people”

Lincoln’s larger claim is this: the Civil War is a test of whether popular government can survive.

He wasn’t only speaking to Gettysburg. He was speaking to the idea of democracy itself—suggesting that if the Union fails, it’s not just America that fails. It’s the belief that ordinary citizens can sustain a nation.

That makes the Gettysburg Address more than national rhetoric. It becomes a universal argument: democracy is fragile, and it has to be defended—sometimes at enormous cost.

How Lincoln’s goals evolved into modern history

Lincoln thought “the world will little note, nor long remember what we say here.” That turned out to be wrong in the most dramatic way.

The speech quickly escaped its original setting and started living new lives.

A) A civic scripture in American education

Because it was short, clear, and morally dense, it became easy to reprint, teach, memorize, and quote. It wasn’t just a Civil War document—it became a lesson in national identity.

B) A measuring stick in political fights

Later generations used “for the people” as a weapon—especially when Americans argued whether government served citizens or powerful interests (for example, debates associated with big business and inequality in the late 19th century).

C) A moral backbone for civil rights movements

The phrase “new birth of freedom” and the Declaration-style equality framing made the address powerful during the Civil Rights Era. It’s hard to deny freedom to some people when you’ve canonized a national speech that says the nation was founded on equality—and reborn through sacrifice.

D) A global symbol during ideological conflict

In the 20th century, the address also became a tool of American messaging abroad, quoted and distributed as a distilled statement of American democratic ideals—especially during the Cold War, when the U.S. wanted to present itself as the moral alternative to authoritarian systems.

In other words: Lincoln’s words became portable. The speech turned into a compact “definition of America” that could travel across decades, movements, and even borders.

Why the Gettysburg Address still hits so hard

Plenty of people gave longer speeches. Plenty offered more detail. But Lincoln did something rare: he compressed a national crisis into a moral equation ordinary people could understand.

- The dead aren’t just dead; they are proof of what matters.

- The war isn’t just war; it’s a test of equality and democracy.

- The living aren’t spectators; they are responsible for the outcome.

That’s why the Gettysburg Address outlived its moment. It wasn’t only a memorial. It was a mission statement—written at the exact moment the nation needed one most.