Europe’s map was never a lucky accident. It was argued into shape—inked by rival chancelleries, sealed with wax and compromise, and enforced by exhausted soldiers stacking their muskets after years of war. Across five centuries, certain agreements did more than end a battle; they reset the rules. The five treaties below didn’t simply close chapters—they opened new ones that still color European politics, borders, and ideas today. Here’s how those signatures changed everything.

The Peace of Westphalia (1648)

The Thirty Years’ War began as a confessional wildfire in the Holy Roman Empire and bloomed into a pan-European struggle that consumed cities, harvests, and faith in old certainties. By the time negotiators converged on Münster and Osnabrück, the continent was starved for a workable peace.

Westphalia’s genius was procedural as much as territorial. Delegations haggled for years, not in a grand hall but in parallel rooms, passing terms like torches through trusted intermediaries. The result was two treaties that did three things with outsized consequences.

First, they recognized a plural religious settlement—Catholicism, Lutheranism, and Calvinism—stabilizing daily life inside the Empire and dulling the blade of sectarian absolutism. Second, they redistributed influence: hundreds of imperial princes gained wider sovereignty in their own domains, even as the Emperor retained a framework for central deliberation through the Imperial Diet. Third, they rebalanced power at Europe’s core. France fixed its eyes firmly on the Rhine and stepped into a century of swagger, while Sweden gained German footholds and a voice in imperial affairs.

Westphalia didn’t end war—nothing so tidy—but it normalized negotiation among many states at once and popularized the habit of treating borders and sovereignty as things to be codified rather than wished into being. The modern diplomatic playbook, messy and necessary, begins here.

Treaty of Paris (1763)

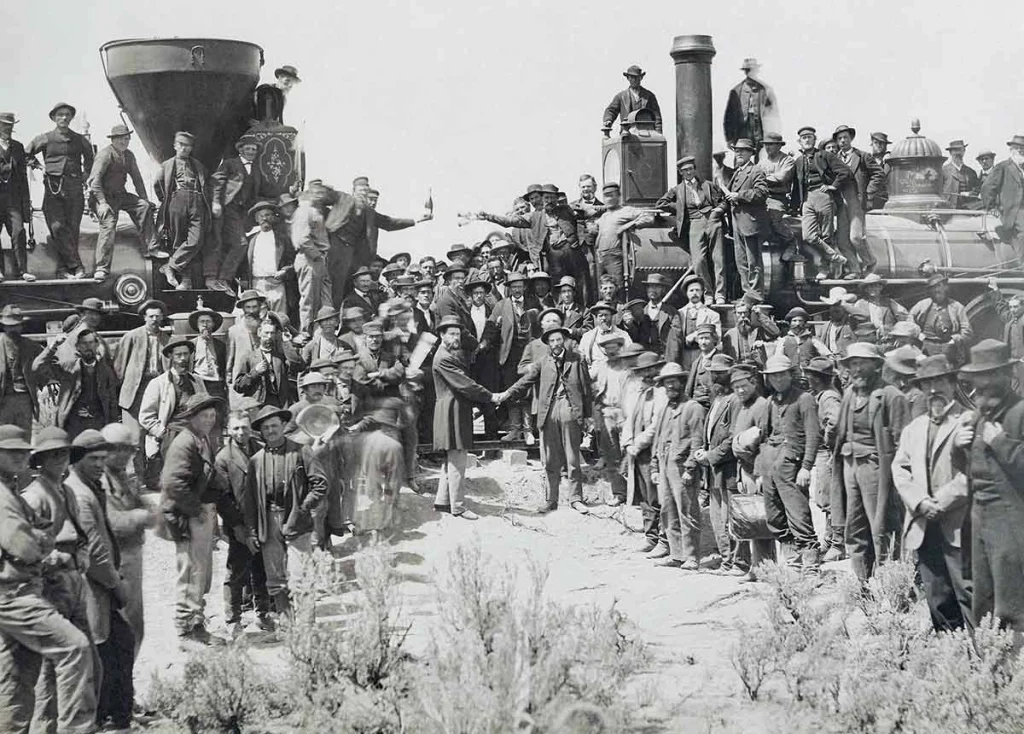

If Westphalia’s aftermath tilted the continent toward France, the Treaty of Paris after the Seven Years’ War swung the world’s door on British hinges. What started as a dispute in North America metastasized into a global brawl: Europe, the Caribbean, India, the seas between. When the guns cooled, Britain and its ally Portugal sat opposite France and Spain; Prussia and Austria settled their own score at Hubertusburg.

The Paris settlement looked, at first glance, like a partial rewind—mutual restitutions, familiar flags back over familiar forts. But the real shift lay across the Atlantic and in Asia. Britain took vast swaths of French North America and tightened its grip on India’s trade and territory. Spain ceded Florida; France’s continental footprint in the New World shrank to a shadow. On paper, the war seemed won; in practice, it had simply moved the bill.

The price of victory—debt piled upon debt—forced Britain to chase revenue from its colonies with a vigor that would prove self-defeating. New taxes, new enforcement, less patience for colonial improvisation: the recipe for rupture. Within a decade, Boston’s wharves had become kindling; within twenty years, Britain was back in Paris—to acknowledge the United States. Yet even in that reversal lay confirmation of 1763’s deeper truth: British power had gone global, and imperial competition would no longer be confined to Europe’s front lawns.

Congress of Vienna (1814–1815)

Napoleon’s rise detonated the old order; his fall left a crater. Into that hole walked Europe’s conservative geniuses of survival—Metternich, Castlereagh, Hardenberg, Nesselrode—and, soon enough, Talleyrand, the wiliest Frenchman alive. Their task: refit a continent shaken by revolution and empire without letting either return in a rush.

Vienna’s congress was less a single treaty than a season of settlement. Its principles were practical: compensate the victorious, contain the disruptive, and connect the great powers in a web of consultation sturdy enough to catch the next crisis before it fell. France was cut back but not carved up—Talleyrand saw to that—while Britain strengthened its maritime and colonial position, Prussia grew in the German lands, Austria reasserted itself in Italy, and Russia absorbed most of Poland.

Two institutional inventions mattered immensely. The German Confederation provided a loose frame over the German states—enough structure to check France, enough slack for Prussia and Austria to compete—later hardening into the skeleton Bismarck would pull into a nation. And the broader “Concert of Europe,” a habit of great-power congresses and consultations, damped continental war for a remarkable run. Reactionary? Absolutely: nationalists and liberals were smothered when they could be. But in cold balance-of-power terms, the system worked. For nearly a century, Europe’s bloodiest wars happened outside Europe.

Berlin Conference (1884–1885)

With Europe relatively stable, its powers turned outward in a coordinated lunge. Africa—mapped by European fantasies long before it was mapped by European surveyors—became the object. The Berlin Conference was called to write rules for a rush most powers had already begun. The “General Act” did not draw every line; instead, it codified how lines would be made and recognized.

To claim was to notify; to notify was to demonstrate control; to demonstrate control was to plant flags, build forts, sign lopsided treaties, and, when necessary, fire guns. This administrative tidiness sanitized conquest for domestic audiences and reduced the chances that Berlin or Paris would fire on London by mistake. It did nothing to reduce violence on the ground against Africans. In the Congo Free State—a private fief dressed up as a humanitarian project—extraction and atrocity were twinned.

For Europeans, the conference accelerated a competition whose sparks would later jump back to the continent: crises in Fashoda and Agadir, nationalist press frenzies, an arms race disguised as empire-building. The map of Africa by 1912 looked like a patchwork quilt of European ambition; the map of Europe by 1914 looked like a powder magazine stacked to the rafters.

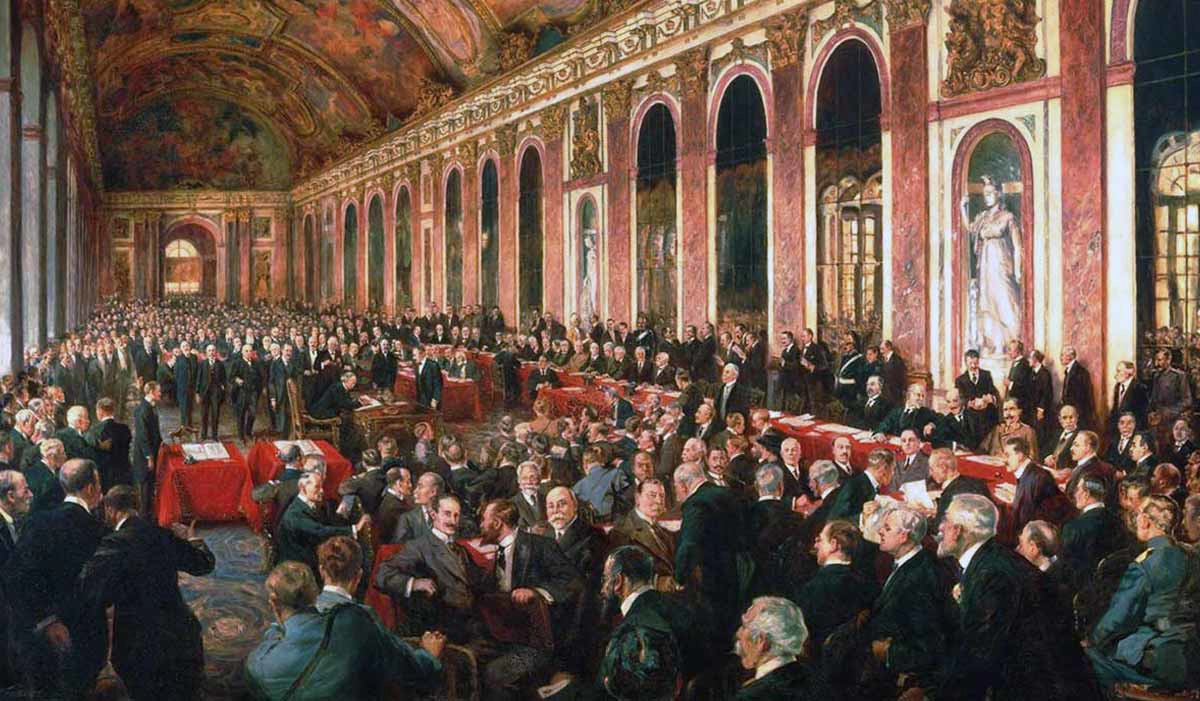

Treaty of Versailles (1919)

World War I ended not with catharsis but with calculation. The Paris Peace Conference convened to make “never again” believable; the Treaty of Versailles tried to fix that into law. Its authors were not of one mind. Wilson brought idealism—self-determination and a League of Nations. Clemenceau brought fear and fury—France had bled in its fields too many times. Lloyd George maneuvered between public appetite for punishment and private worries about balance. Italy’s Orlando wanted promises kept; few were.

Versailles disarmed and dismembered Germany’s power, stripped its colonies, clipped its borders, capped its army, and attached reparations and liability that would fester into grievance. The Habsburg world was dismantled altogether; new states appeared where empires had been—Poland, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia—hopeful and vulnerable at the same time. The League of Nations was the novelty: a forum where disputes might be cooled by procedure rather than bayonet. But without the United States, and with great powers hedging, the League proved more conscience than cop.

Was Versailles too harsh? Too soft? Historians still argue. What’s clear is that it framed the politics of the next twenty years: German revanchism, border controversies in the new states, a global depression that turned discontent into dynamite, and, finally, a second war launched in the name of undoing the first treaty’s constraints. Versailles didn’t cause every calamity that followed—but it furnished the stage, props, and many of the lines.

Treaties Beyond the Core

Not every world-shaping agreement rewires Europe’s center; some rerouted the currents that eventually returned to it.

- Treaty of Tordesillas (1494): A papal-blessed line split new worlds between Spain and Portugal, sending Portuguese sailors toward Brazil and the Indian Ocean and Spanish conquistadors into the Americas. The global empires that followed shifted Europe’s wealth, tastes, and rivalries for centuries.

- Treaty of Verdun (843): The Carolingian heartland fractured into three realms, seeding the cultural and territorial ancestors of France, Germany, and a contested middle belt. Medieval Europe’s jigsaw begins here.

- Treaty of Nanjing (1842): The first “unequal treaty” in China forced open ports and ceded territory, inaugurating a century of imperial intrusion that enriched European powers and normalized a diplomacy of coercion abroad that often fed hubris at home.

- Treaty of Sèvres (1920) / Lausanne (1923): Sèvres sketched the Ottoman Empire’s demise; Lausanne inked a revised reality after Turkish resistance under Atatürk. The post-Ottoman Middle East—mandates, borders, frustrations—was drafted in European rooms and still radiates consequence.

Why These Treaties Still Matter

Treaties don’t only redraw maps; they reshape mental worlds. Westphalia taught Europeans to live with pluralism and to negotiate at scale. Paris (1763) confirmed that empire had gone planetary and that war costs could boomerang into revolution. Vienna wrapped raw power in a process—concert diplomacy—that kept rivals talking and, for a long time, fighting elsewhere. Berlin wrote a bureaucratic gloss over conquest, exporting rivalries that would later be imported back as crises. Versailles, finally, tried to engineer peace by punishing a defeated great power and institutionalizing international cooperation—an experiment that failed in its first form but set precedents the United Nations would later refine.

Across them all runs a thread: Europe’s attempts to balance ideals and interests, values and velocity. Signatures can’t stop history; they can only redirect it. When they channel energy wisely—toward inclusion, consultation, and enforceable balance—the peace lasts. When they ignore resentment, or moral cost, or the limits of power, the ink dries over kindling.

The Long Echo

Stand at any European border crossing, sit in any parliament, read any headline about alliances or enlargement or sovereignty, and you’ll hear these agreements murmuring. The habit of multilateral negotiation, the expectation that borders are legal arguments before they’re military targets, the reflex to convene congresses in crises—these are Westphalia and Vienna living on. The recognition that global power contests don’t stop at Europe’s beaches—this is Paris (1763) and Berlin whispering warnings. The awareness that punitive peace can be precursor to catastrophic war—this is Versailles’ somber lesson.

In the end, treaties are stories Europe tells itself about what it has survived and what it wants to be. The five above mark turning points where the story bent. They remind us that diplomacy is not the absence of struggle but the arena where struggle is civilized—where swords become sentences, and maps, however imperfectly, become promises.