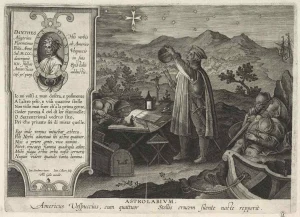

In a ruined palace of Sogdiana in Central Asia – far from Italy – archaeologists discovered a striking mural: a female wolf, head turned back, suckling two human infants. This 8th-century Tajikistan wall painting depicts the legendary scene of Romulus and Remus being nursed by the she-wolf. How did an ancient Roman myth find its way to the Silk Road? Scholars note that Byzantine coins bearing the iconic wolf-and-twins image circulated in Central Asia, inspiring local artists to copy the “Roman pattern”. The myth’s resonance may also have met similar steppe legends: Central Asian tribes like the Wusun and Türks told of abandoned boys nourished by wolves who later became founders of nations . Thus, on the eastern fringes of the known world, Rome’s founding story was recognized as a powerful tale of survival and destiny.

Yet for the Romans themselves, the legend of Romulus and Remus was more than a distant fable – it was the very charter of their city. To understand why, we must journey back to the wooded banks of the Tiber, to an age of kings and omens, where myth and history blur. There, according to Roman tradition, a series of miraculous events led to the birth of Rome and its first king, Romulus.

Aeneas and Alba Longa: Prelude to the Twins

Long before Romulus and Remus, Roman lore traced the city’s ancestry to the heroes of Troy. After the fall of Troy, the Trojan prince Aeneas was said to have wandered to Italy and founded a line of kings. Aeneas’s son Ascanius (also called Iulus) established the city of Alba Longa in the Alban Hills, and his descendants ruled the Latins for generations. In time, King Proca of Alba Longa had two sons: Numitor and Amulius. By custom Numitor, the elder, should have inherited the throne, but Amulius usurped the kingship by force. Amulius then eliminated potential rivals – he murdered Numitor’s sons and forced Numitor’s daughter Rhea Silvia to become a Vestal Virgin, sworn to lifelong chastity. By imprisoning Rhea Silvia in the Vestal order, Amulius meant to cut off Numitor’s lineage and secure his stolen crown.

It is at this point that destiny intervened, at least as the Romans told the story. Ancient writers like Livy remark that perhaps the Fates had already decreed the origin of this great city – for despite Amulius’s precautions, the stage was set for the birth of Rome’s founders.

The Birth of Romulus and Remus

According to the legend, the princess Rhea Silvia somehow became pregnant, breaking her Vestal vows. She declared that the father of her unborn children was Mars, the god of war . Livy notes skeptically that she might have named Mars “either because she believed it, or because a god as father made a better excuse” for her condition . In any case, Rhea Silvia gave birth to twin boys – Romulus and Remus – an event the Romans viewed as divinely ordained. King Amulius, however, was enraged. He saw the twins, of royal blood, as a direct threat to his rule. He ordered the infants to be put to death.

Not wishing to spill royal blood directly (which could bring a curse), Amulius commanded servants to abandon the twins to nature. The newborns were placed in a wooden trough and carried to the swollen Tiber River to be drowned. It was early spring, and the Tiber had overflowed its banks, turning the low-lying land into a floodplain. The servants, unable to reach the main river channel, left the basket in a shallow lagoon formed by the floodwaters, expecting the infants would perish in the rising tide.

Here fate (or fortune) intervened. The flood receded rather than rose, and the twin boys survived. Their cradle drifted to the edge of the flooded area and came to rest at the foot of a wild fig tree – the Ficus Ruminalis, as later Romans called it. (“Ruminalis” was associated by folk etymology with ruma, “teat,” for reasons soon apparent.) This spot was near the future Lupercal, a cave on the slope of the Palatine Hill, and at that time it was a lonely, marshy nook far outside any town.

There, the most famous moment of the myth unfolded. As the infants wailed, a she-wolf (lupa in Latin) came upon the scene. Rather than harm the babies, the wolf instinctively treated them as her own pups. She lay down, offered her teats, and suckled the twins gently, even licking them clean. This extraordinary tableau – the two human infants nourished by a wild wolf – struck the Romans as a sure sign of divine favor. Later Roman authors remarked that it was fitting the boys were saved by the creatures of Mars. In Roman religion the wolf was sacred to Mars, and so was the woodpecker; some versions of the story said a **woodpecker alighted nearby and brought morsels of food to Romulus and Remus as well . To pious minds, these nurturing animals proved that the god of war was indeed the twins’ father, watching over his children in the wild.

Soon after, according to Livy, the king’s chief shepherd, Faustulus, found the twins. He had spotted the she-wolf with human babies and was astonished to see the creature behaving tamely. Faustulus carefully approached and snatched up the boys, and the wolf slunk back into the woods. (In memory of this encounter, the fig tree under which the wolf had let the twins nurse was cherished and fenced off by Romans for centuries.) Faustulus carried the infants home and presented them to his wife, Acca Larentia, and the couple raised Romulus and Remus as their own sons.

Later ages tried to rationalize the miraculous elements of this story. Both Livy and Plutarch mention a tradition that Acca Larentia had been a prostitute (in Latin slang, lupa – a “she-wolf”) and that the tale of a literal wolf suckling the boys arose from a sort of pun or misunderstanding. In this interpretation, it was a human woman nicknamed “Wolf” who nursed the twins – a more plausible scenario to some ancient skeptics. But Livy himself, while noting these variant theories, treats the miracle as the version “generally received”. The image of the wolf and twins was so potent that it became the emblem of Rome itself, celebrated in sculpture and coin for ages to come. As one modern historian writes, “there is no evidence concerning the historicity of the Romulus and Remus mythology” – and yet the Romans wholeheartedly believed that the gods (through a wolf) had saved their founders for a great destiny.

Raised by a She-Wolf: The Twin Heroes Grow

Romulus and Remus grew up in humble circumstances, unaware of their royal birth. They lived with Faustulus and Acca Larentia, who were shepherd folk in the region of the Palatine Hill. The twins spent their childhood among shepherds and cattle herders, roaming the wooded hills and learning to survive off the land. From early on, they showed exceptional strength and leadership ability. Plutarch recounts that as the boys came of age, “they were both courageous and manly…but Romulus seemed more shrewd and political, born to command rather than obey” . The brothers and their rustic companions hunted game in the forests and defended their flocks from wild predators.

As teenagers, Romulus and Remus began to confront a different kind of threat: human bandits. The hills around Alba Longa were infested with brigands who stole cattle and ambushed the local farmers. The twins, with youthful boldness, organized the shepherds into a band to resist these raiders. Livy writes that the brothers would even ambush the brigands, recover stolen goods, and share the loot with the needy shepherds – acts that made them popular among the hill-folk. Soon a band of loyal youths formed around Romulus and Remus, attracted by their prowess and generosity. Unbeknownst to all, the two young leaders were actually the grandsons of Alba Longa’s deposed king – but fate was about to reveal their true identity.

The catalyst came during an annual festival. Every year, the locals celebrated the Lupercalia, a pastoral fertility festival in honor of Pan/Faunus, which involved young men running naked around the Palatine. Romulus and Remus took part in the Lupercalia festivities. Meanwhile, a group of the very brigands the twins had been thwarting saw an opportunity for revenge. They laid an ambush. In the scuffle that ensued, Romulus fought them off, but Remus was captured – the brigands knocked him unconscious and delivered him to King Amulius in Alba Longa, falsely accusing Remus of being a rural raider caught stealing Numitor’s flocks.

Amulius handed the captive Remus over to Numitor, his dispossessed elder brother, for punishment (perhaps as a way to humiliate Numitor by letting him execute a bandit). Numitor, now an old man, questioned Remus and was struck by the youth’s noble demeanor. Some versions say that Remus, in custody, mentioned his unusual upbringing – how he and his twin brother had been found and raised by a shepherd after being washed up by the Tiber’s flood. Numitor’s heart must have pounded as he recalled the long-ago day when his infant grandsons had been taken to the Tiber. He quickly pieced together the clues (twins of the right age, a mysterious rescue) and suspected Remus was his grandson. Separately, the shepherd Faustulus, alarmed at Remus’s capture, finally confessed to Romulus that he and his brother were of royal blood – Faustulus had known ever since he found them that the timing and circumstances matched the exposure of Numitor’s grandsons.

With the truth unveiled, Romulus acted swiftly. He gathered a band of their stout-hearted shepherd friends and persuaded Numitor to support an uprising. Romulus, likely joined by Faustulus and a small force, rushed the city of Alba Longa from one side, while Numitor arranged for Remus to be freed and armed on the inside. In a dramatic coup, the twins and their allies attacked the palace. King Amulius was taken by surprise and slain in the fighting. The usurper’s reign was over.

Immediately afterward, Numitor called the Alban people together and revealed what had happened: how Amulius had seized the throne years ago, how Numitor’s own grandsons survived by miracle and had now returned, and how Amulius had met his end. Numitor was restored to the kingship of Alba Longa amid general rejoicing, with Romulus and Remus saluting him as king and hailing him as their grandfather. The people of Alba accepted the two heroic youths as Numitor’s kin and the rightful avengers of injustice. The old order was set right.

Romulus and Remus had thus rescued their family’s honor and brought justice to Alba. Numitor was back on the throne, and one might think the twins would remain in Alba Longa as princes and heirs-apparent. But the twins’ destiny lay elsewhere – in the place of their miraculous childhood. They soon became “seized with the desire to found a city” of their own in the region where they had grown up. In Livy’s words, “After the government of Alba was given back to Numitor, Romulus and Remus were seized with the desire to build a city in the place where they had been exposed and raised”.

Several reasons are given for this decision. Livy notes that Alba Longa and the surrounding Latin towns had excess population, and many of the young men – including the duo’s band of followers – were eager to have their own new settlement rather than live under Numitor’s shadow. The twins themselves, now full of ambition, likely preferred to be rulers in a fresh colony than merely junior nobles in Alba. And so, with Numitor’s blessing, Romulus and Remus set out with a contingent of settlers to found a new city on the site of the Palatine Hill, above the Tiber, where their lives had been saved.

Founding the City of Rome

The twin brothers returned to the hills by the Tiber – the area of the Seven Hills – to establish their city. They chose the general locale of the Palatine, where the she-wolf’s Lupercal cave and the fig tree were located. But almost immediately, sibling rivalry reared its head again. The brothers could not agree on which hill should host the new city’s acropolis, nor on who would have the honor of naming and leading the city. Romulus preferred the Palatine Hill, the center of his youthful domain; Remus favored the Aventine Hill, a bit further to the south. This dispute led them to seek a divine sign to resolve the matter.

They resorted to the ancient Italic ritual of augury – interpreting the will of the gods by observing the flight of birds. Each brother took position on his chosen hill (Romulus on the Palatine, Remus on the Aventine) and watched the skies, vowing to accept Jupiter’s verdict. As the story goes, Remus was the first to see an omen: six vultures flew overhead on his side. Shortly thereafter, Romulus observed twelve vultures flying by his station. Both men immediately claimed victory – Remus argued that he saw his six birds first (timing was the divine signal), whereas Romulus argued that he saw more birds (number was the decisive sign). Their followers on each hill saluted their respective leader as the chosen king, and a heated argument ensued when the two parties came together.

The augury contest had failed to peacefully appoint a single leader. Tensions flared, and what began as a verbal quarrel between brothers degenerated into a brawl between their supporters. In the chaos, Remus was killed. The accounts of this final confrontation differ in their details and blame. Livy gives the famous version: Remus, bitter and mocking, stepped over the line of the furrow that Romulus had begun to plow for the city’s boundary. In contempt, Remus leaped over Romulus’s new wall, saying it was so low even a brother could jump it. In a flash of rage, Romulus struck him down. “So perish whoever else shall leap over my walls!” he cried – a grim warning that trespassers and usurpers would meet the same fate. Remus fell dead, and Romulus was sole victor. (In another version, one of Romulus’s lieutenants named Celer dealt the killing blow at Romulus’s behest, making Remus’s death slightly less fratricidal. And Dionysius of Halicarnassus, a Greek historian of Rome, suggests Remus died in the melee by an unknown hand during the scuffle between the rival groups. Regardless of who struck the blow, all sources agree that Remus died on the spot and Romulus survived as the founder of Rome.)

With Remus’s tragic end, Romulus faced the reality that he had effectively sacrificed his twin to fulfill his own destiny. Later Romans had mixed feelings about this fraternal bloodshed – seeing it as both terrible and, in a way, necessary for the birth of their city. The mythmakers tried to give the story a moral logic: Romulus’s infamous act removed the last rivalry and ensured Rome would have one king. In Livy’s narrative, Romulus is heavy-hearted but proceeds with his great work. He gives Remus an honorable burial and names a site, Remoria, after him (one obscure tradition even claimed Remus’s spirit founded a small town Remuria, but this variant never became mainstream). Henceforth, the city would be Romulus’s alone – Roma, named after its first king.

Romulus now formally founded the new city. Roman tradition fixed the date of Rome’s founding as April 21, 753 BC, a date celebrated annually as the city’s birthday (the festival of Parilia, an old spring shepherd festival, was adopted as Rome’s natal day). Romulus performed the foundation rites in the Etruscan manner, having learned them, according to Plutarch, from religious experts from Tuscany. First, a circular trench was dug on the future site of the Comitium (assembly place). Into this trench – the mundus – were cast sacrificial first-fruits of all the necessities of life, along with small clods of earth that each settler had brought from his home region. This ritual symbolized the gathering of people from different origins into one community, and sanctified the ground of the new city.

Next, Romulus yoked a white bull and a white cow to a plow with a bronze plowshare. He plowed a deep furrow marking the boundary of the nascent city, tracing a sacred line (the pomerium) around the hill. By custom, all the clods were turned inward to mark the city’s future wall, and the furrow itself was considered holy. Wherever a gate was planned, the plow was lifted, leaving a gap in the furrow so that the pomerium was unbroken except at those designated entrance points. The pomerium ritual defined Rome’s initial limits – according to tradition, Romulus’s original city encompassed the Palatine Hill in a rough square, later reverently called Roma Quadrata (“Square Rome”). Ever after, Romans would regard the act of plowing the pomerium as the true birth of the city – a mystical moment when Rome was separated from the wilderness around it. Romulus’s plow had drawn a line between civilization and chaos, between Roman and not-Roman, that would endure and expand with the city.

With these rites, Rome was founded. Romulus, at roughly age 18 (if one follows the later chronology), became the first King of Rome. He stood as the sole leader of a small but determined band of settlers – a mixed group of Latins from Alba, other Latium folk, and runaway slaves and adventurers who had joined his cause. They built huts on the Palatine and began the work of organizing their new community. Romulus’s legendary act of fratricide cast a shadow, but it also inaugurated the city with a kind of grim resolution: the rule of law (symbolized by the wall) would be upheld even at great personal cost. As Romulus later supposedly proclaimed, Rome was to be an eternal city, and no one – not even a brother – would be allowed to subvert it.

The First King of Rome: Romulus’s Reign

Having founded the city, King Romulus set about fortifying and populating it. He and his followers built simple dwellings – wattle-and-daub huts with thatched roofs – on the Palatine. (The Romans preserved the memory of Romulus’s shelter; even in the Imperial era, a modest thatched hut called the Casa Romuli stood on the Palatine, said to be the remains of Romulus’s own house, restored over time.) The immediate concern was manpower: Rome needed people. According to legend, Romulus declared his settlement an asylum – a sanctuary for exiles, fugitives, and runaway slaves from anywhere in Italy. Displaced persons and ne’er-do-wells flowed in, grateful for a fresh start under Romulus’s leadership. This gave Rome a reputation from the outset as a haven for society’s outcasts, but it also rapidly increased the population. The city’s early inhabitants were predominantly male, rough around the edges, and fiercely loyal to Romulus who had given them refuge.

To give his rough citizens structure, Romulus is credited with establishing many of Rome’s earliest institutions. He organized the able-bodied men into a militia. In Roman tradition, Romulus formed the first Legion, comprising 3,000 infantry and 300 cavalry (the horsemen called Celeres, “the swift,” perhaps after the comrade Celer who helped him). He also selected one hundred of the wisest, oldest men to form a council of advisors – the Senate. These men he called Patres (“Fathers”), and their descendants became the hereditary Patrician class of Rome. The Senate would function as an advisory body to the king, lending prestige and continuity to the monarchy. By calling his senators “Fathers,” Romulus symbolically made them guardians of the nascent state, establishing the concept of an aristocratic class with ancestral responsibility for Rome’s welfare.

Additionally, Romulus is said to have divided the common people into tribes and curiae (voting wards) to organize civic life. Later Romans believed there were initially three tribes in Rome: the Ramnes (Romans of Romulus), the Tities (Sabines of Titus Tatius), and the Luceres (perhaps a mix of Etruscans or later arrivals). In fact, Plutarch reports that the very name tribus (tribe) indicates “three,” preserving the memory of Rome’s first tripartite social division. Two of those tribes, as we shall see, came from a dramatic event a little after the city’s founding: the union with the Sabines.

Despite the influx of asylum-seekers, one problem loomed large: women. The community of Romulus’s asylum was overwhelmingly male. To secure the future of Rome, marriages and children were needed. Romulus first attempted diplomacy. He sent envoys to the neighboring towns (including the Sabine communities) requesting marriage alliances – essentially asking the neighbors to allow their daughters to marry Romans. These requests were rebuffed; the haughty neighbors looked down on Rome’s motley band of exiles and brigands and feared strengthening the upstart city by intermarriage. The rejection stung. Romulus then resorted to a strategem that would become infamous in legend: the abduction of the Sabine women.

Romulus announced a grand festival – the Consualia, in honor of the god Consus – and invited the people of the surrounding towns, including the Sabines, to attend as guests. Lured by the prospect of games, feasting, and religious observance, a large number of Sabines (men, women, and children) and others from nearby Latin towns came to Rome’s festival. According to Livy, at a prearranged signal during the games, Romulus’s men rushed into the crowd and seized the young women of the visiting families . Each Roman bachelor grabbed a Sabine (or Latin) maiden. The women, wailing, were carried off to become wives of the Romans. The distraught fathers and brothers fled the city in outrage and sorrow once they realized they had been duped and their daughters taken.

This event – often termed the “Rape (Abduction) of the Sabine Women” – was not a rape in the modern sense of immediate violence, but rather a mass forced betrothal. Romulus pacified the sobbing women by promising them honorable marriage, civil rights, and a share in the property and destiny of Rome. He spoke to each personally, according to Livy, assuring them that this seizure was out of love for their beauty and the desire to make them Roman wives, and that they would be happier as wives of Romans than as unmarried girls in their parents’ homes. Over time, the legend says, the women did come to accept (even love) their new husbands – a crucial detail, as it sets up the next twist of the story.

The enraged fathers of the women, however, were not mollified. In particular, Titus Tatius, king of the Sabine people of Cures, assembled an army to avenge the insult and recover their women. War broke out between the Sabines and Romulus’s Romans. Initially, the Sabine army launched a clever assault on Rome’s citadel (the Capitoline Hill). A Roman maiden, Tarpeia, betrayed the citadel to the Sabines – she opened the gate, allegedly seduced by the promise of “what was on their left arms.” She meant their gold bracelets; the Sabines, disdainful of traitors, crushed her to death under their heavy shields (worn on the left arm) as they marched through the gate. Tarpeia’s name lived on in infamy (the cliff from which traitors were later hurled in Rome was called the Tarpeian Rock). With the Capitoline captured, the Sabines under Tatius clashed with Romulus’s forces, who held the Palatine. A fierce battle ensued in the valley between (the future Forum).

At one dramatic moment in this battle, Romulus prayed to Jupiter for help and vowed to build a temple to Jupiter Stator (“Stayer”) if the Romans held their ground. The Romans rallied, and the fight with the Sabines raged on equal terms. But the decisive intervention came not from a deity but from the Sabine women themselves. By now, some months had passed since their abduction, and many of the Sabine women had become wives of the Romans – some even pregnant or with newborns. These women now performed one of the most courageous acts in Rome’s early legends: they rushed onto the battlefield, coming between their Sabine fathers and Roman husbands, tearing their hair and pleading for peace.

Livy movingly describes how the women cried out that they now had kinship with both sides – they bore Sabine blood but were wed to Romans – and a war between their loved ones was unbearable. “Better for us to die than to live as orphans or widows,” one Sabine woman (Hersilia, Romulus’s own wife) reputedly shouted. Their sudden appearance and heartfelt entreaties stopped the combat cold. Ashamed and moved, the warriors on both sides laid down their arms. Romulus and Tatius conferred and agreed to unite their peoples rather than continue fighting over the women. A grand peace was forged: Sabines and Romans would merge into one nation, with joint kingship and joint citizenship. The kidnapped women thus became the bond that tied the two peoples together.

Under this agreement, Titus Tatius the Sabine king co-ruled with Romulus. The Sabines joined the Romans in Rome, effectively doubling the city’s population and strength. The Capitoline Hill became home to the Sabines (Romulus had the Palatine; Tatius took up residence on the Capitoline near the future Temple of Juno Moneta). The two kings ruled side by side, and the people were known collectively as Quirites – a name deriving from Cures, the Sabine city of Tatius, to honor the Sabines’ equal inclusion. Romulus integrated the Sabine men into his army and their nobles into his Senate. The Roman tribes were reconfigured: one tribe (the Tatienses) was named for Tatius’s Sabines, alongside Romulus’s original Ramnes, and a third called Luceres (of more obscure origin, possibly Etruscans or later recruits). Thus, Rome became a dual community, Latin and Sabine together.

For a few years, Rome had two kings. Romulus and Tatius were said to govern in harmony, each respecting the other. Plutarch notes that there was only one notable disagreement: when some relatives of Tatius violated the law by robbing and killing ambassadors from Laurentum, Romulus wanted to punish them, but Tatius sheltered them, causing a rift. Shortly after, in retaliation for that crime, Tatius was assassinated by a group of angry Laurentians while attending a sacrifice. He was struck down at Lavinium (another city in Latium) five years into the joint kingship. Romulus’s own life was spared, and he responded by giving Tatius an honorable burial in Rome and diplomatically dismissing the murderers (some whispered that Romulus did not mind being rid of his colleague, but nothing is definitively stated) . Importantly, the Sabines did not revolt or secede after their king’s death. They remained united under Romulus’s sole leadership, which suggests – in the myth’s logic – that by then the two peoples had truly fused into one state. Rome was one kingdom again, under King Romulus, but forever shaped by its bi-cultural origin. The episode of the Sabine women became a core Roman legend emphasizing that from strife came unity. It was a national parable of reconciliation: the first Romans were both conquerors and conciliators, turning enemies into citizens.

Romulus went on to rule Rome for many years. In the narrative handed down by later Roman historians, Romulus’s reign lasted 37 or 38 years (from 753 BC to about 716 BC, by Varro’s chronology). During this time, he supposedly strengthened the city, led successful wars against hostile neighbors (the Etruscan city of Veii, the Fidenae, and others), and expanded Roman territory. He is credited with bringing the Caelian Hill within the city and perhaps founding the port of Ostia (though some attribute Ostia to later kings). Many of Rome’s oldest temples and rituals were ascribed to Romulus’s era as well – for instance, the Temple of Jupiter Stator, vowed during the Sabine war, and the institution of the Ferronia games.

As years passed, however, the legends say Romulus grew more imperious. He was a successful warrior-king and began to take on a dictatorial manner, acting less consultative with the Senate. The ancient sources hint at rising discontent among the Roman nobles. Romulus was still admired by the common folk and the army, but the patres (senators) resented that he sometimes bypassed them. There was whispering that Romulus had become too autocratic.

Then came a mysterious end to his reign – one wrapped in mystery and divinity. One day, Romulus reviewed his troops on the Campus Martius (Field of Mars) near the Goat’s Marsh, when a sudden and violent thunderstorm rolled in. The sky turned black, thunder boomed, and a whirlwind swept through. The assembled Romans scattered in fear. When the storm passed, Romulus had vanished. The soldiers and citizens searched for their king, but Romulus was nowhere to be found – no body, no trace.

In the stunned silence after this cosmic event, the Romans began to murmur: had the king been struck by lightning? Carried off by the gods? Or – as some darkly suspected – murdered by treacherous hands in the confusion? The senators, who had been standing near Romulus, claimed they hadn’t seen what happened; some later rumors hinted that perhaps they seized the opportunity to kill Romulus and hide his remains. Plutarch reports that “some conjectured that the senators…fell upon him and slew him, then cut his body in pieces and carried each a portion away under their robes”, explaining why no corpse was found . But this was never proven, and it remained a shadowy conjecture.

To calm the public panic, one of Rome’s leading men – Julius Proculus, a senator and reputed friend of Romulus – stepped forward with a proclamation. Shortly after the storm, Proculus swore, he had encountered Romulus in a transcendent form. The king appeared to him, glowing in regal armor, and told him that he had been taken up to the heavens by his father Mars. Romulus, so Proculus claimed, bade the Romans to cease mourning and instead worship him as a god under his new name, Quirinus, promising to watch over Rome from above. Upon hearing this, the Romans – who desperately wanted to believe their beloved founder was not gone forever – were overcome with religious awe. They hailed Romulus as a godling and Son of Mars, and they formally established the cult of Quirinus, installing Romulus among the pantheon of Roman deities. The people “went away rejoicing” that Romulus was now a benevolent god rather than a lost king. In the decades and centuries to follow, a great temple of Quirinus stood on the Quirinal Hill, and Romulus was venerated on certain holidays as one of Rome’s divine protectors.

Thus, Romulus did not receive a grave, but a cult. His disappearance was painted as an apotheosis – a fitting end for a hero. In the Roman mind, this put Romulus in the company of heroes like Hercules (who was also believed to have become a god after death). The mix of awe and skepticism about Romulus’s end is evident in our sources: Livy says “no one ever doubted that Romulus gave his name to the city; most modern historians believe his name a back-formation” (hinting that Romulus might be a mythical eponym) and acknowledges the many variations of the story. But the version officially embraced was that Romulus ascended to heaven.

Plutarch notes that after Romulus’s apotheosis, some Romans experienced a twinge of regret or doubt about the possible foul play, which manifested in strange phenomena (like sudden darkness and storms) until rites were performed to appease Romulus’s spirit. In any case, Romulus’s earthly reign was over, and the Romans were left with a legacy – a city, named Roma after Romulus, and a new god to watch over them. The subsequent king, Numa Pompilius (a Sabine chosen to succeed Romulus), would emphasize peace and religion, complementing the warlike foundational era of Romulus.

With Romulus, the mythic phase of Roman history comes to a close. The key elements of the legend – divine parentage, miraculous survival, fratricide, and ascension to godhood – established a template that was rich in symbolism. Rome was born through trial and triumph, violence and unity, and its first king became a god who would forever safeguard the city he founded.

Myth and Reality: Historical and Archaeological Context

How much of the Romulus and Remus story is history, and how much is myth? Modern scholars generally regard the tale as a mythical charter, not a literal account of events . The earliest written sources for the myth appeared in the late 3rd century BC, many centuries after the supposed founding in 753 BC. By that time, Rome had long been a republic expanding across Italy, and its origin story had likely evolved through oral tradition and political storytelling. Key elements – twins, a she-wolf, fratricide – have the hallmarks of legend rather than eyewitness memory. As one historian succinctly puts it, “There is no evidence concerning the historicity of the Romulus and Remus mythology”.

That said, archaeology and comparative history suggest kernels of truth embedded in the myth. The site of Rome was indeed inhabited in the mid-8th century BC – right around the legendary era of Romulus. Archaeological evidence shows that the area of the Palatine Hill and its surrounding valleys saw a merging of small villages in the 9th–8th centuries BC . Rome did not spring fully formed in one day; it grew from the gradual union of several hilltop communities during the Final Bronze Age and early Iron Age . Historians believe that around 750–700 BC, these settlements coalesced into an urban entity – the early city-state of Rome. This broadly aligns with the timeline later assigned to Romulus. It’s possible that memories of this unification and the power struggles that accompanied it were later distilled into the drama of two rival brothers, one of whom must kill the other for the city to unite under a single ruler. The fraternal conflict could symbolically represent factional conflicts between different tribes or villages in prehistoric Rome. As the scholar T. P. Wiseman and others have noted, Romulus’s very name looks suspiciously like an eponym (it essentially means “Mr. Roman”), suggesting he personifies the Roman people, while Remus may have been invented or adapted to embody a rival group or to add a tragic dimension to the foundation story .

The Romans themselves were not naïve about the implausibilities in their founding legend. Livy, writing around 25 BC, prefaces his account by acknowledging that the stories of gods begetting children and wild beasts nursing infants are perhaps “poetic marvels.” Yet he defends their inclusion, saying “if any nation ought to be allowed to claim divine descent, it is Rome”, and he treats the legend as a matter of national faith . Livy hints that believing in Romulus’s divine parentage and the wolf’s providential care elevates the story of Rome’s birth, in line with the city’s later greatness. He then dutifully recounts the tale, wolf and all. This reflects an attitude among Roman historians: a blend of skepticism and reverence. They knew the foundation myth was a sacred story, crucial for Rome’s identity, regardless of factual accuracy.

Interestingly, some archaeological discoveries have lent credibility to parts of the legend. In the 20th century, archaeologist Andrea Carandini excavated on the slope of the Palatine and found remains of a very ancient wall and gate. In 1988, Carandini announced he had uncovered a stone wall dated to the mid-8th century BC, precisely where the historian Tacitus wrote that Romulus’s original pomerium was located . The wall, about 2.5 meters thick, along with post-holes and foundation trenches, suggests the Palatine settlement was indeed fortified in that era . Carandini even identified what he believed was the “Wall of Romulus.” While we cannot be certain it’s the same wall of legend, its dating and location are a striking match to the myth. “We will never discover the wall of Romulus, because Romulus is a legend, of course,” Carandini conceded – but, he added, “the nucleus of the legend is right…we proved this because nobody believed that there really was a fortification of the Palatine Hill” . In other words, a core element of the Romulus story (the building of a city wall on the Palatine) appears to reflect a real event in Rome’s proto-history.

Another archaeological gem came in 2007, when Italian archaeologists announced they likely found the Lupercal cave itself. Working with subterranean scans near the ruins of Augustus’s palace, they discovered a vaulted cavity 16 meters underground – a grotto decorated with seashells, mosaics, and a painted white eagle on its ceiling . This richly decorated cave lies on the Palatine slope, in the area ancient authors placed the Lupercal (and indeed, a record from the 16th century noted that such a cave existed there and was restored by Augustus) . The find strongly suggests that Augustus – who styled himself a renovator of Rome’s traditions – identified and sanctified the Lupercal as part of Rome’s heritage, possibly even using it for ceremonies. The Culture Minister of Italy at the time said, “This could reasonably be the place attesting to the myth of Rome…the legendary cave where the she-wolf suckled Romulus and Remus” . While the cave’s exact identity is still debated, its discovery shows how tangible the myth became in Rome’s topography. The places of the legend – the fig tree, the Lupercal cave, the line of the pomerium – were not abstract. They were concrete locations in the city that Romans revered and preserved.

Moreover, material culture demonstrates that the Romulus and Remus story was firmly entrenched by the early Republic. A silver didrachm coin dated to around 269 BC (during the Third Samnite War period) depicts a she-wolf with twins . This indicates that by the 3rd century BC – likely earlier – the image of the wolf nursing the founders was a recognized symbol of Rome . Over the next centuries, this motif appeared frequently on Roman coins, reliefs, and sculptures, reinforcing the legend’s prominence. The Romans even exported the image abroad: coins of the Constantinian era (4th century AD) showing the wolf and twins have been found far and wide, and the theme was copied beyond Rome’s borders. The mural in Sogdiana is a case in point – 8th-century Sogdian artists painting a wolf with twins, likely inspired by Byzantine coins that had reached Central Asia . Golden pendants with the wolf-and-twin design from the 6th century have been found in what is now Uzbekistan, confirming that the “Roman twins” became part of a shared visual language along the Silk Road .

Ultimately, while no archaeological evidence can confirm a real Romulus or Remus, the early urbanization of Rome and certain rituals (like infant exposure, or a memory of conflict between communities) provide a believable backdrop for the myth. The story as we have it is an artful blend of Italic folklore, perhaps influenced by Greek myths (the exposure of infants recalls stories like Perseus or Oedipus, and the she-wolf has parallels in legends of infants nurtured by animals, such as the founder of the Arcadians, Telephus, who was suckled by a deer ). The Romans, practical as they were, accepted that the details might be embroidered – for example, some rationalized the she-wolf as Acca Larentia and the woodpecker as merely a helpful passerby – but they clung to the essence: that Rome was born under miraculous circumstances, which marked it for greatness.

As historian Mary Beard notes (paraphrasing scholarship), the Romulus myth is not historical fact but historical narrative – a story the Romans told about themselves. It served to explain and glorify aspects of Roman culture: why Romans considered themselves children of Mars (warlike and valiant), why their city incorporated diverse peoples (thanks to the asylum and Sabine merger), why Roman society had a patrician class (traced to Romulus’s first Senate), and even why Romans performed certain rituals (the Lupercalia, the Parilia on April 21st as “birthday of Rome,” the Larentalia in honor of Acca Larentia each year in April) . In short, the myth became a charter myth – a foundational tale that legitimated Roman institutions and values.

Evolution of the Myth in Roman Culture

Throughout the centuries of Roman civilization, the founding myth of Romulus and Remus continually evolved, adapted, and inspired. In the Republican era, Roman statesmen and writers often invoked Romulus’s name. During crises, some Romans dreamed of a “new Romulus” to save the state. For example, after the civil wars, there was a suggestion that Octavian (the future Augustus) might take “Romulus” as a title, positioning himself as a second founder of Rome. (He declined that name due to its fratricidal baggage, opting for Augustus, but the very suggestion shows how potent Romulus’s image was in Roman political thought.) Augustus did consciously link himself to Romulus in other ways: he reportedly renovated the Hut of Romulus on the Palatine and celebrated the city’s foundation day lavishly, underscoring that under his reign Rome was reborn and renewed, much as it had been born under Romulus.

Roman writers of the 1st century BC to 1st century AD integrated the foundation myth with Rome’s broader epic history. Virgil’s Aeneid, commissioned by Augustus, makes a masterful connection between Aeneas (the Trojan progenitor) and the twins. In Book 1 of the Aeneid, Jupiter prophesies to Venus that a descendant of Aeneas, a priestess, will bear twin sons to Mars – clearly Romulus and Remus – and that Romulus will found the city and give it his name, and Rome’s empire will have no end. By doing this, Virgil tied the Romulean myth into the Trojans’ saga, giving Rome a dual heritage: one strand from Troy (via Aeneas) and one purely Italian and divine (via Mars and the Latin princess). This fusion became the accepted “big picture” of Roman origins – Aeneas to Alba Longa to Romulus’s Rome . The Trojan side provided antiquity and connection to the Greek heroic world; the Romulus side provided a uniquely Roman, local legitimacy and connection to Mars.

During the late Republic and Empire, the story was recounted by many historians and embellished in different genres. Ovid in his Fasti (poetic calendar) tells of the festivals related to the legend: the Lupercalia, Parilia, and others, often rationalizing or gently questioning the old stories. Livy gives a sober prose version (with occasional doubts expressed, as we saw). Dionysius of Halicarnassus, a Greek writing in Augustan Rome, tries to reconcile the tale with Greek sensibilities, downplaying the supernatural (he even floats the idea that Remus was not killed by Romulus but died later, or that Romulus’s mother might have been secretly deflowered by a mortal man, not Mars ). Each author adapted the myth to their audience and purposes: to moralize, to glorify Rome, or to provide etiologies (origin explanations) for Roman customs.

One notable theme that Roman commentators often addressed was the fratricide. Romulus’s killing of Remus was morally awkward – how could the founder of Rome also be a murderer of his own brother? The Romans offered several interpretations to digest this. One, as mentioned, was that it was actually someone else (like Celer) who killed Remus, absolving Romulus of direct guilt . Another was that Remus brought it on himself by his impious action of leaping over the wall – thus Romulus acted in righteous anger to defend the city’s sanctity. A third spin was that Remus’s death was fated by the gods. Later writers, and possibly earlier annalists like Ennius, framed the conflict as destined – Romulus had to triumph, Remus had to fall, for Rome to be united and indivisible. The historian Livy suggests an underlying lesson: in the struggle for primacy, only one can rule – a somber reflection that may have resonated during Rome’s civil wars, when Romans shed each other’s blood for the state’s future. In a sense, Romulus and Remus prefigured Cain and Abel (a parallel often noted by later Christian writers) – a foundational fratricide that marks the human condition. But unlike Cain, Romulus is not cursed; in Roman eyes, he is justified and even deified . The paradox was absorbed into Roman culture: Rome’s greatness was worth the cost of Remus’s life, and the end (a strong Rome) justified the means. As Brewminate’s analysis puts it, “Even though he committed fratricide, Romulus was acclaimed and revered…because the murder of Remus by his brother was fated by the divine and essential for Rome’s rise to greatness” . The myth thus imparted a rather stark value: the state transcends family, an idea that indeed often played out in Roman history (Romans regularly celebrated heroes who sacrificed their sons or brothers for the republic or empire).

The cultural impact of the myth within Rome was immense. Every year on April 21 (marked as 21 Aprilis), Romans celebrated the birthday of Rome (dies natalis Urbis Romae). In the late Republic, this was done with modest sacrifices; under the Empire, it became a lavish festival. Emperor Hadrian in AD 121 held extraordinary games for Rome’s 874th birthday (since he calculated it from 753 BC) . Coins were issued depicting the she-wolf and twins suckling, with legends like “ROMA AETERNA” (Eternal Rome). By then, the she-wolf and twins had been a symbol of the city for at least a millennium. The Lupercalia on February 15 also continued into the Christian era (until finally suppressed in AD 494). During that festival, the Luperci priests would sacrifice goats and a dog at the Lupercal cave, smear themselves with blood, and run around the Palatine striking women with goat-thongs to promote fertility – a bizarre ritual that the Romans themselves linked to the time of Romulus and the nursing wolf (the Luperci were said to be re-enacting the wild, unbridled vigor of the foster-animal that raised the twins). The Larentalia (December 23) honored Acca Larentia, the foster-mother, reflecting the more humanized version of the tale . And the Parilia, originally a shepherds’ spring festival, was repurposed as the Founding Day of Rome. Under Emperor Claudius, Antoninus Pius, and others, these traditions were reinforced – for example, the Secular Games often referenced Aeneas and Romulus toasting the continuity of Rome from its first day to the current emperor’s reign .

The myth also permeated art and literature. Countless Roman works depicted the infancy of Romulus and Remus. In the Forum, a statue group of the twins and wolf stood (by tradition, the Ficus Ruminalis and a bronze wolf statue were displayed in the Forum, though the famous bronze Capitoline Wolf statue may have been crafted later). The image appeared on the shields of legionaries, the badges of the Legio XIII Gemina (one of Caesar’s legions) featured the twins and wolf, and it was carved into reliefs celebrating Rome’s origins.

Even beyond antiquity, the Renaissance revived the story with gusto. As Rome became a center of art once more, painters like Peter Paul Rubens, Pietro da Cortona, Nicholas Mignard, and Sebastiano Ricci all portrayed scenes from the twins’ saga . They relished the dramatic contrasts: the feral wolf with gentle maternal instincts, the innocent babes, the rugged shepherd discovering them, the tragic duel of the brothers. The Capitoline Museums in Rome today display a bronze statue of the she-wolf (the Lupa Capitolina), which for a long time was thought to be an Etruscan masterpiece from the 5th century BC. Modern analysis suggests the wolf portion might actually be a medieval (13th-century AD) creation, with the twin figures added in the 15th century AD . Even if that particular statue is medieval, it testifies to the enduring power of the image – the fact that a medieval sculptor (or restorers in the Renaissance) deliberately crafted or modified it to include the twins shows that the legend never faded. Indeed, the she-wolf and twins have remained the emblem of the city of Rome into the 21st century.

The Legacy of Romulus and Remus

The story of Romulus and Remus has transcended its ancient origins to become one of the best-known myths in world history – a tale told alongside the likes of the founding of Athens or the adventures of Hercules. Its legacy is woven into the identity of Rome, aptly nicknamed the “Eternal City.” For Romans of antiquity, the myth affirmed that their city was born of divine providence and human valor. It gave them Mars as a divine ancestor, a wolf as a nurturing symbol, and Romulus Quirinus as a protector god. It explained the city’s name, its mixture of peoples, and even its social structure. As Livy remarks, the legend was “embellished” but cherished, and in Roman times it was “celebrated and discussed” on every April 21st at birthday ceremonies .

Today, we read the myth not as literal history but as a rich narrative – part heroic epic, part folktale, part moral allegory. We see in it themes that resonate widely: twins whose fates are intertwined but ultimately opposed (a motif found in many cultures), the quest for power and its costs, the importance of law (walls) in civil society, the integration of outsiders (as in the Sabine women episode), and the notion of sacrifice for a greater good. The myth has been compared to others: the Biblical Moses, set adrift in a basket on the Nile, comes to mind when Romulus and Remus float down the Tiber; the Babylonian king Sargon had a similar infancy legend of river rescue; the Persian Cyrus the Great was said to have been suckled by a dog; and numerous legends in the Indo-European world feature heroes or founders nursed by wild animals . The Romulus and Remus tale, in its particular Italian setting, may have drawn on some of these archetypes or sprung from common mythic impulses – reflecting how societies imagine their origins to be touched by the divine or the extraordinary.

For the city of Rome, Romulus and Remus remain eternal figures. Walk through Rome today, and you will find their likeness on civic buildings, fountains, and souvenirs. The wolf and twins symbol is on Rome’s coat of arms and the logo of its football club A.S. Roma. The Palatine Hill still has an area called the “Hut of Romulus,” where tourists hear the tale of the city’s first moments. The Forum has the Lapis Niger, a black stone that Romans believed marked Romulus’s grave or perhaps the spot of his ascension. The Via Sacra (Sacred Way) was said to be where the final battle between Romulus and Tatius’s forces turned in Rome’s favor when Jupiter Stator was invoked – and a small archeological site by the Arch of Titus may be the foundation of the Temple of Jupiter Stator that Romulus built in thanks.

In the end, whether Romulus was a real person or an amalgam of many, his name will forever be linked with Roma. The myth of Romulus and Remus, raised by a wolf and torn apart by fate, encapsulates the spirit of Rome: bold, fierce, and singularly determined to endure. As the ancient poet Ennius wrote, “Romulus in his city Remusque priore relinquunt” – “Romulus in his city, Remus left behind” – a poignant line acknowledging the cost of Rome’s birth. From that sacrifice grew an empire. And through the lens of myth, we glimpse how Romans understood themselves: as a people chosen by the gods, tempered by adversity, and destined to leave a monumental legacy. The twin brothers at the river’s edge, one day alive by a miracle and another day tragically at odds, gave Romans a narrative to make sense of their own complex origins.

Blending narrative storytelling with historical analysis, we see the myth of Romulus and Remus is more than a legend; it was a tool of identity, a political legitimization, and a cultural treasure passed through the generations. Its evolution over time – from oral tale to written epic to state ritual – illustrates the flexibility and power of myth in human society. And even stripped of its factuality, it conveys truths about human nature and civic life.

The founding of Rome, as told through Romulus and Remus, remains a compelling saga. It reminds us that great cities often have mythic beginnings, where reality and imagination meet. Standing in the forum at twilight, one can almost picture a she-wolf’s silhouette on the Palatine and hear the distant cry of an infant – a faint echo of Rome’s primordial story. The myth endures, much like Rome itself, inviting each new generation to find meaning in the timeless tale of the twin brothers, the wolf, and the Eternal City they began.

Sources:

- Livy, Ab Urbe Condita (History of Rome), Book 1 – sections on Rhea Silvia’s twins, the wolf, and the founding of Rome .

- Plutarch, Life of Romulus – a biography blending various legends of Romulus, including alternative versions .

- Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities – a Greek perspective on Rome’s early history, citing multiple founding tales .

- Archaeological reports and modern scholarship on early Rome’s development and the find of the Palatine wall , as well as the discovery of the Lupercal cave .

- Cultural analyses of the myth’s significance: e.g., Brewminate (2020) on the fratricide and its interpretation , and Wikipedia summaries on the founding of Rome and its later celebration .

- Numismatic and artistic evidence of the wolf-and-twins motif from ancient coins and Central Asian murals , underscoring the myth’s wide diffusion and longevity as a symbol of Rome.