In the early 1800s, life at the United States Military Academy at West Point was tightly controlled. Cadets were expected to be models of discipline and morality. Alcohol was strictly banned on campus, and even smoking tobacco could hurt a young officer’s chances of graduating.

On paper, it was a school of rules.

In reality, it was full of young men eager to break them.

By 1826, West Point’s 260 cadets had developed a reputation for drinking. So when Christmas rolled around that year, the leadership decided something had to change.

The Christmas Eggnog… Without the Eggnog

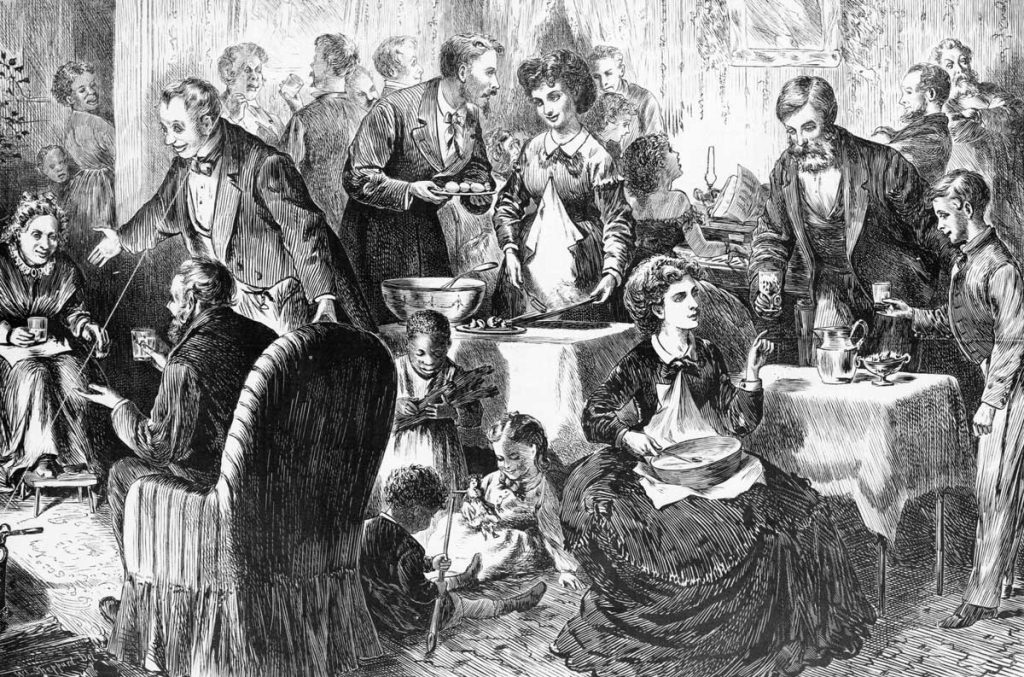

Christmas at West Point traditionally meant eggnog — and not the tame sort. Eggnog at the time was usually loaded with rum, and George Washington himself was said to drink a version spiked with rum, brandy, whiskey, and sherry.

Superintendent Sylvanus Thayer, determined to restore order and sobriety, made a deeply unpopular decision:

That year’s Christmas eggnog would be alcohol-free.

To Thayer, it was a sensible disciplinary measure.

To the cadets, it was a declaration of war.

A Secret Supply Run

If the Academy refused to supply drink, the cadets would simply get it themselves.

A group of them slipped off to Benny’s Tavern, a nearby establishment that had no interest in West Point’s rulebook. There they bought:

- Two gallons of whiskey

- One gallon of rum

The contraband was smuggled back into the North Barracks, and on Christmas Eve, the real celebration began.

At first it was just a forbidden party: whispered jokes, clinking cups, and spiked “eggnog” flowing freely in the shadows of a supposedly sober academy. But as the night went on and the alcohol took hold, things escalated.

support our project

At History Affairs, we believe history belongs to everyone.

Your contribution helps us keep this global archive open, free, and growing — so people everywhere can learn from the past and shape a better future.

From Party to Riot

By about 4:00 a.m. on Christmas Day, the mood in the North Barracks was loud, rowdy, and impossible to ignore. Officers on duty finally moved in to investigate.

Captain Ethan Allen Hitchcock, realizing things were spiraling out of control, decided to put a stop to it. He formally read the Riot Act – a legal warning used to order an unlawfully assembled crowd to disperse.

The cadets did not disperse. They didn’t even calm down.

Instead, they mocked orders, argued, and shoved. A small fight broke out. While the officers tried to restore discipline in the North Barracks, the chaos spread.

In the South Barracks, another officer, Captain Thornton, tried to break up the festivities. He was attacked and knocked unconscious for his efforts.

The situation was no longer just a drinking incident. It was now a full-blown mutiny against authority.

The rioting cadets then turned their attention back to Captain Hitchcock. They rushed his room, smashed his windows, and in the confusion a pistol was fired. Whether it was meant as a warning shot or something more serious, it was enough to end any illusion that this was harmless fun.

At that point, arrests began.

Christmas Morning at West Point

Reveille on Christmas morning usually meant order, neat ranks, and precise formations.

In 1826, it meant something very different.

The parade ground and barracks were a mess of broken glass, splintered furniture, and hungover cadets. Many were in no condition to stand, much less march. The military academy that prided itself on discipline woke up to one of the most embarrassing scenes in its history.

The so-called “Eggnog Riot” had done real damage — not only to property, but to reputations and careers.

More reading

Consequences: Careers Broken and Futures Shaped

The fallout was swift and severe.

In the investigation that followed:

- Six cadets resigned

- Nineteen cadets were court-martialed

- Ten were expelled

Among those caught up in the scandal were men who would go on to become important figures in American history, including:

- Two future Confederate generals

- A future Supreme Court justice

And then there was Jefferson Davis, who would later become the President of the Confederate States of America. Davis wasn’t expelled, but he didn’t come away unscathed: like many others, he was confined to quarters for more than a month.

For some, the Eggnog Riot ended military careers before they began. For others, it became an early, embarrassing footnote in otherwise remarkable lives.

A Riot Over a Drink

On the surface, the Eggnog Riot of 1826 looks almost ridiculous: a group of future officers turning Christmas into chaos just to drink spiked eggnog.

But behind the absurdity, it reveals a familiar tension:

Young men living under strict rules, eager to assert their independence, and willing to push back—hard—when authority goes too far.

Superintendent Thayer wanted to stamp out drunkenness and harden discipline. Instead, his attempt at control triggered one of the most infamous episodes in West Point’s history.

All over a holiday drink that was supposed to be alcohol-free.

support our project

At History Affairs, we believe history belongs to everyone.

donateYour contribution helps us keep this global archive open, free, and growing — so people everywhere can learn from the past and shape a better future.

know the present

Defense Tech Needs the State, Not Less of It

Trump Era or The New Imperial Age

America First, Venezuela, and the Trap of Old Habits

Why the AI Race Has No Winner

reading more

Machiavelli, Luther, and the Rise of Modern Moral Thought

First Steps in Philosophy: A Guide for Beginners

The Qin Dynasty (221 – 206 BCE): Era of Legalism in Chinese History

Knights vs. Samurai: Origins, Codes, and the Real Lives Behind the Armor

The Epic Italian Campaign: From Mussolini’s Downfall to the Liberation of Rome

Story of the First Legend Hero: Cadmus

The United States and Political Intervention in Latin America

The Third Century Church: Growth, Persecution, and Transformation

The Nazi-Soviet Pact: A Deal with the Devil

Assisted Dying: Righteous Act or Not?

Ancient Medicine and the Four Humors

The Sacred Power of Medieval Queens